Spectrum pricing is one of the biggest bugbears of the GSMA, and its latest report is another opportunity for the lobby-group to wag the finger of disapproval at governments trying to replenish bank accounts at the expense of connectivity.

July 17, 2018

Spectrum pricing is one of the biggest bugbears of the GSMA, and its latest report is another opportunity for the lobby-group to wag the finger of disapproval at governments trying to replenish bank accounts at the expense of connectivity.

The ‘Spectrum Pricing in Developing Countries’ report, released by the GSMA Intelligence unit, puts forward familiar arguments from the association, which of course represents the interests of the telcos. Whenever the GSMA has a bee in its bonnet you have to take any criticism with a pinch of salt, but it is difficult to argue with some of the evidence and conclusions which have been put forward here.

“Connecting everyone becomes impossible without better policy decisions on spectrum,” said Brett Tarnutzer, Head of Spectrum at the GSMA.

“For far too long, the success of spectrum auctions has been judged on how much revenue can be raised rather than the economic and social benefits of connecting people. Spectrum policies that inflate prices and focus on short-term gains are incompatible with our shared goals of delivering better and more affordable mobile broadband services. These pricing policies will only limit the growth of the digital economy and make it harder to eradicate poverty, deliver better healthcare and education, and achieve financial inclusion and gender equality.”

The view must be exceptional atop that incredibly high-horse… but there is a point to the self-righteous proclamation.

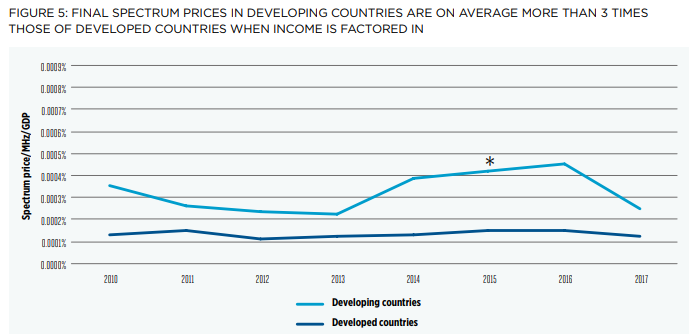

As you can see from the graph above, the trends are quite clear. When the GDP of the country is taken into account, the adjusted cost of spectrum licenses are three times higher in developing nations than in the developed ones. There will of course be several reasons for this, not just greedy governments trying to bolster spreadsheets as the GSMA seems to be implying, but it is not a correlation which makes sense.

These are countries where mobile infrastructure is under-developed, therefore significant investments need to be made to kickstart the digital evolution. Spending more of spectrum licenses reduces the amount (in theory) an operator can spend on the infrastructure, while it would also be a fair assumption to assume lower national GDP means lower ARPU for the operators. In a perfect world, every government should be able to reclaim the same amount on spectrum sales in each of their auctions, but generally life is not fair. Reserve prices and annual license fees have to be adapted to the market to make an attractive business case for the operators.

What is worth noting is it is not every developing nation which is getting the policy decision making wrong, and in some cases the lessons have been learned. But there are consequences.

Jamaica is an example of where high reserve prices caused chaos. With a reserve price of $40 – 45 million set in 2013 for 700 MHz, the auction was ignored by the operators. A year later, the government corrected its mistake, though the launch of 4G networks was delayed until 2016 as a result with Jamaica’s 4G penetration today less than half that of the average throughout the Caribbean. Mozambique is another, which offered a total of 50 MHz in the 800 MHz band for the reserve price of $150 million. Operators would have had to invest a third of their annual mobile service revenues to meet the starting bid, which was concluded to be completely unfeasible. This is a country where the situation has not been rectified, 4G is yet to be launched, though the National Communications Institute of Mozambique plans to launch another auction during 2018.

The case for cheaper spectrum licenses has been made many times by the GSMA. The argument from operators and the GSMA that more would be spent on infrastructure with lower license expenses is theoretically sound, though sceptical individuals might suggest the penny pinching telcos are just looking for another way to spend less. However, there are examples where the boy who cried wolf might have spotted some teeth; it’s hard to argue with some of the figures presented by the GSMA here.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

_1.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=800&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)