The Informer was amused to listen to a recent news bulletin on Radio 4. The newsreader, in impeccable, clipped, RP English, gravely announced that the boss of Twitter – one Dick Costolo – has conceded that his company “sucks” at dealing with trolls. The incongruity of a BBC announcer delivering American slang in the same voice as he would use to report on the Royal Family was just perfect.

February 6, 2015

By The Informer

The Informer was amused to listen to a recent news bulletin on Radio 4. The newsreader, in impeccable, clipped, RP English, gravely announced that the boss of Twitter – one Dick Costolo – has conceded that his company “sucks” at dealing with trolls. The incongruity of a BBC announcer delivering American slang in the same voice as he would use to report on the Royal Family was just perfect.

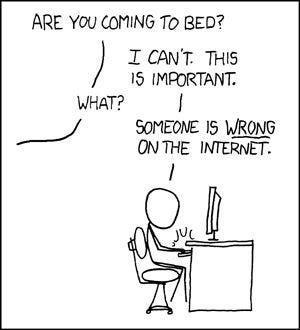

The story itself was also intriguing, not that you would have guessed from the neutral tone in which it was delivered. For the uninitiated, troll is a word used to describe people who are gratuitously abusive online. The cause can be varied and often it’s just a matter of people arguing a point to a histrionic degree. The internet seems to enable this kind of dogmatism and it’s perfectly illustrated by one of the Informer’s favourite cartoons from xkcd.

But Costolo was referring more to the premeditated, malicious kind of correspondence that seems to blight Twitter especially. These are people who seem to extract a kind of sadistic pleasure from inflicting misery on others and are emboldened by both the relative anonymity and the geographical separation afforded by the internet. These people would presumably not speak in the same way to their victims’ faces and there have been amusing examples of trolls being confronted in ‘real life’ by the recipients of their malice.

Famously a boxer called Curtis Woodhouse, tired of being abused on Twitter, tweeted: “I’ll give £1000 to anybody that provides me with address and picture of this man”. Having got the address Woodhouse drove there and even tweeted a photo of the street sign, by which time the troll had completely lost his nerve, prompting Woodhouse to add the hashtag #jimmybrownpants to his tweets. The troll ended up capitulating completely and pleading for mercy – an immensely satisfying outcome.

Another extreme troll incident seems to have provided the catalyst for Costolo’s mea culpa. Columnist Lindy West was the recipient of the sustained attentions of an especially vindictive troll and despite advice not to ‘feed’ the troll by acknowledging them, she chose to write about the experience. The troll read it and was so moved that he wrote an apology to West and vowed to immediately change his trolling ways.

Without presuming to know how much compassion Costolo feels for individual victims of trolling, he will also have been alarmed by the PR implications of stories such as those detailed. Social media companies have long argued, quite legitimately, that they are just the medium and can’t be held responsible for what people publish. But they do already have to curate content on their site to get rid of illegal stuff, so it’s also a bit disingenuous of them to claim editorial impotence.

The challenge they have, as does the broader internet, is finding the ideal balance between unfettered self-expression and quality control. In his (deliberately?) leaked internal memo Costolo said: “We’re going to start kicking these people off right and left and making sure that when they issue their ridiculous attacks, nobody hears them.” All very laudable, and definitely a PR win for Twitter, but you have to wonder where this crusade will lead. How will Twitter distinguish between malicious trolls and merely opinionated bores? How will it prevent abuse of the reporting process? To what extent will it police political correctness?

In spite of the outpouring of defiance in the wake of the attack on the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, we live in increasingly censorious times. The immediate response of the French government to the attack was to arrest anyone who publicly defended it and stories condemning public figures for saying the wrong thing online are a daily occurrence.

There are a lot of unpleasant people out there and the internet has made it easier than ever for them to inflict that unpleasantness on others. But increasing the levels of censorship on the internet could just drive the bad guys underground, while at the same time preventing a lot of interesting, constructive discourse from taking place, so the Informer hopes companies like Twitter tread carefully in their war on trolls.

Read more about:

DiscussionYou May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

_1.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=800&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)