The story of LTE may be all about data, but voice remains a lucrative, core service for mobile operators. Bringing voice services to LTE is far from straightforward, with numerous choices to be made and challenges faced.

July 9, 2013

Dealing with the data explosion is well established as the central challenge of the mobile operator community and its suppliers. So fundamental has this become to the narrative of the mobile industry that anyone joining the story at this point could be forgiven for not realising that people still use their mobile phones to talk to one another.

The commercial reality of mobile voice is that revenues are headed south—but they are far from trivial. Globally voice revenues may have been decreasing for some time but Informa forecasts that voice will still account for more than half of all mobile operator revenues out to 2017, when global revenues are expected to hit $1.16tn, of which more than $584bn will derive from voice.

On the service side voice has been all but ignored. Traditional industry voice innovation flatlined long ago; all of the running in recent years has come from internet players and independent application developers. After years spent trying to splice data capabilities into networks with voice-based DNA the industry is now looking at the ways in which it can carry on providing core, lucrative voice services on a network platform—LTE—designed exclusively for data.

The irony is that, in LTE, operators have created a platform even more capable of delivering enhanced voice services created by OTT innovators than that which preceded it. In mobilising to solve their capacity crunch issues they have cleared a path for talented competitors and left themselves challenged in the provision of their core service. Voice over LTE (VoLTE) is intended as the solution to these problems.

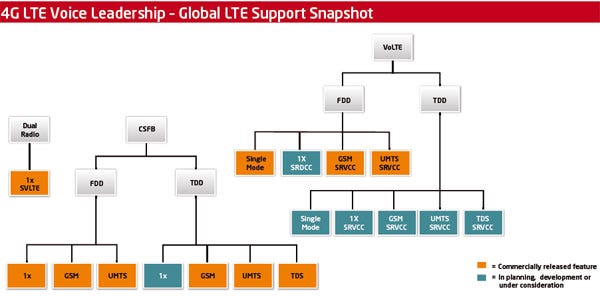

If only it where that simple. In reality VoLTE is more of a concept than a specific service—a series of pathways rather than a destination. From full Voice over IMS to dual radio handset solutions, Qualcomm has identified 17 different ways to provide a voice service from an LTE handset (opposite), bringing us back to familiar industry issues of fragmentation and interoperability. So much for the harmony of a single, global standard.

Factor in the reality that different operators will choose which of these paths to follow at different times in different markets and the result is even more convolution.

Voice over LTE is one of the most complex technologies being deployed within the framework of the LTE roadmap, says Peter Carson, senior director for marketing at Qualcomm—although this alone does not set it apart. “VoLTE is no different from any other new technology development, with one exception,” he says. “And that is that you’re talking about the business that has been the historical core of the mobile industry, honed and refined over the past 20 years, to the point where it is virtually indistinguishable from wired telephony in quality and reliability. And that’s a very high bar.”

As it is, mobile voice isn’t broken and it doesn’t need fixing—and it certainly doesn’t need replacing with a service so immature as to be of lesser quality, reliability or reach. But operators have no option but to move to VoLTE at some point, because the move to LTE in a wider sense is imperative.

There are two drivers pushing operators to VoLTE deployments, and they carry different weight depending on the operator in question and depending on who you talk to. The first is network consolidation: It is economically inefficient to operate networks on multiple standards in the medium to long term. Once LTE deployment gathers true, industry-wide momentum operators will be motivated to migrate users over as fast as the technology allows. And that means driving down legacy voice networks, not least because it will free up spectrum for refarming.

The second driver is service-related. Many within the industry believe—or at least are arguing—that operators need to develop a suite of richer, unified communicatons services, in which VoLTE is the voice element, to make them more competitive with internet application innovators.

And while OTT players have been successfully marketing just these kind of services for some time, the argument runs, mobile operators should be able to exploit their strengths in standardisation, interoperability and quality of service to differentiate network-based enhanced communication services from competition that runs over the top.

Michel Lenoir is programme manager for LTE at Vodafone Netherlands. “This is about enabling more communications services for our customers, on one network, hopefully,” he says. “Better QoS, better control over the call, the ability to open data sessions, add video streams, this kind of RCSe fucntionality.

The VoLTE network would be a perfect carrier for these kind of services. And we can better control the customer experience when these services are in our own network. That’s the driver for us.” Not everyone believes in RCS, or RCS combined with VoLTE, however. Dean Bubley, founder of consultancy Disruptive Analysis is among the most vocal critics. “There is zero benefit—and quite a lot of cost—to RCS as a standalone app. The contention that it will somehow encourage people to give up using WhatsApp, KakaoTalk, Line and the other messaging platforms is risible,” he wrote in a recent blog post. “Blending it with VoLTE will further delay and complicate an already-struggling (and much more important) system; the two should be kept 100 per cent separate until either/both are well-established.”

Qualcomm’s Peter Carson opts for a more diplomatic assessment, although he can’t help a knowing chuckle when he says: “There are some things you can do with IMS and VoLTE that represent enhancements, and you could argue that RCS enables the kind of services that the OTT providers have been marketing for quite some time.” For Carson the real benefit for operators lies in reliability, seamlessness and cross-carrier portability—something that remains years into the future.

If history teaches us anything, says founder of industry consultancy Northstream, Bengt Nordstrom, it is that the telecoms industry takes time to deliver new services. “The issue with voice and messaging solutions from the operator community and the standardisation bodies that specify them is that our lead time to take something to market is generally five to seven years,” he says. “No matter how important VoLTE is we’re not going to see it in the mainstream until 2016, because the legacy base is zero VoLTE phones.”

The first steps have been taken, however. There have been two VoLTE launches in South Korea, from SK Telecom and Korea Telecom, and one from US operator Metro PCS. AT&T has suggested that it will launch later this year, while Verizon has committed to launching by early 2014 at the latest.

For operators with a CDMA legacy, early moves are driven by a need for network consolidation. VoLTE is a long way from mainstream, says Peter Carson, and these first iterations are “running very fast, without any bells and whistles; without anyting that would distinguish VoLTE from a 2G or 3G call.”

Operators elsewhere remain relatively relaxed about the move to VoLTE. Vodafone’s Michel Lenoir says: “The first demos are promising but it’s at least a year or a year and a half until we see VoLTE coming into the market.” In the interview on page 10, Telstra’s executive director for networks and access technologies Mike Wright says that he is happy to be a follower rather than a leader in VoLTE. “We don’t have a strong driver,” he says. “If we’re just reproducing existing voice services it’s not that exciting. But we’re ensuring that we’ll be ready technically when we see critical mass in terms of devices and compelling capabilities.” But vendors suggest that there is a noticeable uptick in operator plans for VoLTE.

Mark Windle, head of marketing at telecoms software player OpenCloud, which is working with Vodafone Netherlands on service continuity between LTE and legacy systems, thinks operators are accelerating their VoLTE plays. “Our perception is that it has changed dramatically in the last nine months,” he says. “Prior to that there was a scramble to launch data-only LTE services, but operators now seem to be going full steam ahead with VoLTE using IMS.”

Thorsten Robrecht, head of portfolio management at Nokia Siemens Networks, agrees. His conversations with customers challenge the assumption that all operators will, to begin with, rely on Circuit Switched Fallback (CSFB), a dual network approach to voice provision.

“Operators that are beginning LTE deployments now are questioning whether they should go to CSFB or straight to Voice over IMS. If we look back five or six years the IMS market was collapsing after some very high expectations. But in the last half year it’s really booming again and the momentum today is mostly around Voice over IMS.”

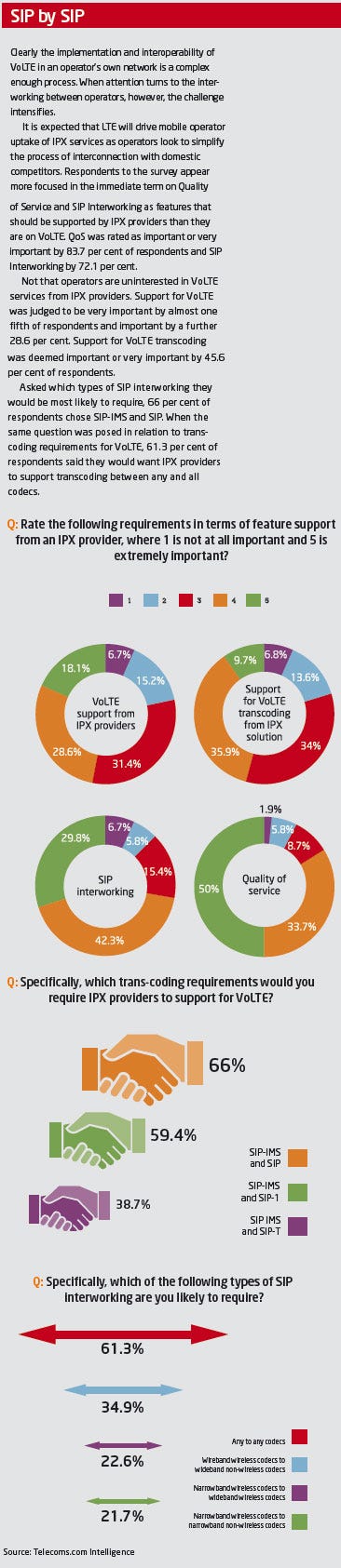

The various routes to VoLTE create choices that will have a significant impact on timings. In a recent survey of operator attitudes to VoLTE, Telecoms.com Intelligence uncovered diverse assessments of the best interim steps.

In contrast to Robrecht and Windle’s assessments, the survey of more than 100 operators suggested that the majority will indeed look first to CSFB. 62.3 per cent of respondents said that they would be deploying CSFB initially, before Voice over IMS. However, a significant number—17.9 per cent—plan to move straight to VoIMS. It is likely that these operators will be among the later movers to VoLTE and to LTE in general. It is also possible that these are operators in smaller markets, says Ajay Joseph, chief technology officer at iBasis. “There may be operators that go directly to VoIMS but I think that will be seldom. Maybe if you have a small network, in a single country or region it will be the right approach. But to do it across all of the market the size of the US, or across a large international footprint, is going to be quite a challenge”

There was a smaller, yet noteworthy, showing in the survey for the use of CSFB alone, with 12.3 per cent of respondents saying that their plans for Voice service in an LTE world did not involve moving beyond reliance on their legacy networks.

Qualcomm’s Peter Carson believes that the full range of solutions for voice in an LTE environment will coexist for some time. “The tail in terms of these other services winding down is going to be quite long,” he says. “CSFB is well established, it’s across every major handset that’s out there, and it’s going to be the lowest common denominator in roaming, for example, for many years to come. In fact we’re seeing a second wave of CSFB deployments from CDMA operators. KDDI has it, and Sprint is going that way. And it will be even more important for the GSM/WCDMA operators.”

As with previous generations of network technology, LTE is being deployed in islands by most operators. So it is likely that, at some point, operators will have VoIMS in some areas of their network but will be limited to CSFB in others. This presents another connectivity headache as operators need to ensure that any call which begins in one environment can be sustained as the user moves to the other. The solution to this is Single Radio Voice Call Continuity (SRVCC) and results from the Telecoms.com Intelligence survey suggest that it divides the industry.

Just under 30 per cent of respondents believe it to be a priority and they are planning its deployment within six months of VoLTE launch.

And yet 23.6 per cent of respondents said that they had no plans to implement SRVCC at all. One quarter of respondents said they would implement it within a year of VoLTE and 21.7 per cent said it would be implemented at some stage, but not within the first year.

Choice of stepping stones aside, there are a number of other challenges facing operators in the VoLTE deployments. Interoperability between standards, operators and across international borders are familiar issues and device availability, as well as problems with power consumption and performance, will also need to be addressed.

The biggest challenge as far as Michel Lenoir is concerned is service parity; deciding how and whether to transition individual legacy voice services to the new domain. The move to VoLTE gives operators a chance to reassess their voice services portfolio but the range of options open to them is wide and they must be clear about which services they want to keep and how best to maintain them, Lenoir says. “With all the IN-based voice services in our core network we need to decide what we’re going to do with them,” he says. “Do we port them into an IMS domain and, if so, how? Do we secure interworking with the circuit switched domain and the new IMS domain? There are all sorts of options and, for me, this is the most challenging discussion that we have.”

Some services may be wound down but others are “so key to the user experience”, Lenoir says, that they have to be maintained.

Some can be ported across to VoLTE while for others the service logic might remain in the legacy network requiring Vodafone to “try to build a proxy” for them.

OpenCloud’s Mark Windle says this process is made more difficult by gaps in the LTE standard. “There are parts within the standards for VoLTE relating to how IMS networks and legacy networks interoperate where the standard effectively says ‘we don’t know how to do this, it will be done by some unspecified magic in the service layer’,” says Windle. “Operators have to find a way of doing that themselves and best practice will hopefully emerge.”

Windle highlights one example in particular; interoperability between the Home Location Register in the GSM/WCDMA network and the equivalent Home Subscriber Server in LTE. In order to maintain seamless services across both networks these two components need to be synchronised but, says Windle, they don’t contain all the same data, and it’s not in the same format in both instances.

“There’s a real-time data synchronisation problem between the two domains here and the answer, in the standard, is left as an exercise for the reader,” he says.

Solving internal interworking problems is only the beginning, however; operators have to interwork with one another as well. If operators are going to create a realistic defence against OTT voice innovation, there has to be ubiquity of service. The industry needs to back itself to solve this problem effectively and efficiently, says Peter Carson, as it has a wealth of experience in addressing similar issues.

“This is an area where the mobile industry has the most experience,” Carson says. “It has a proven track record, even in situations where you’ve had divergent standards, as with short messaging. The industry worked out those interoperabilty issues and created seamlessness in text messaging—they’ve done it every time there’s been a new service. But it will take several years before we have mainstream interoperable VoLTE services along those lines.”

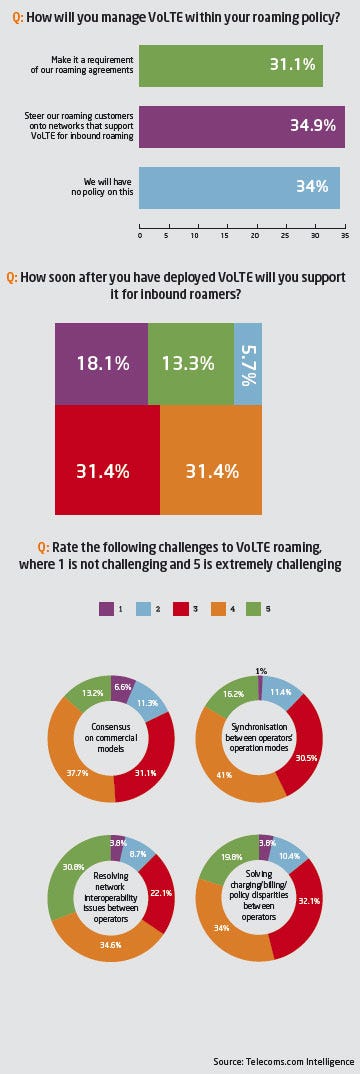

Cross-border functionality is the next step. International roaming is a hygiene factor for today’s mobile consumers, and mobile operators need to decide how they are going to manage the continuity of VoLTE services for both inbound and outbound roamers (see box, Going Global).

Whatever progress is made with networks and services, nothing can happen without devices. With only three commercial VoLTE services in play, the number of compatible devices is small. “Availability is very limited at the moment,” says Michel Lenoir. “Most are still in beta testing or lab testing mode; it’s too early. Next year will be a different story, though.”

Indeed NSN’s Thorsten Robrecht believes devices vendors are preparing to ramp up production. “I am seeing unbelievable movement on the devices, especially around VoLTE. It’s a very hot topic at all the device suppliers.”

It needs to be, as there is much to address, says Qualcomm’s Carson. Power consumption and battery life are particular issues, he says. “It is very complicated trying to conserve power in a VoLTE call,” Carson says. “There are certain features built into standards, like discontinuous reception where you shut the transceiver off for short intervals and this is very challenging to optimise. It takes months, or even quarters, to optimise these algorithms to fully extract power gains, even from features that are specfically designed to preserve power.”

But there are signs of improvement in this area. Test and measurement specialist Spirent recently released results of tests conducted on the Metro PCS network of first- and second-generation VoLTE devices from Korean supplier LG. The average cuurent drain on the first generation device, the LG Connect, during a VoLTE call was 356mA. For the second generation device, the Spirit 4G, the figure was 232mA. Battery life was estimated at 575 minutes (talktime) for the newer device, and 259 for its predecessor.

The industry is used to blaming handset vendors for delays in the commercialisation of new network technology but, in the case of VoLTE, this would be unreasonable. The truth is that VoLTE is complex across the board, from the device back to the core network. The industry is more than up to the challenge of addressing that complexity, and needs to do so as part of its wider, longer-term migration to LTE.

If there are question marks hovering anywhere it is over the value the service will bring to operators in terms of competitive differentiation. And as long as the majority of operators are holding the VoLTE door open for others rather than rushing through it themselves, those question marks look like they’re being taken rather seriously.

Read more about:

DiscussionAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

_1.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=800&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)