The most likely future relationship between the two superpowers will neither go back to the hyper-globalised world nor revert to the earlier model of business conducted on national level entirely insulated from one another.

February 17, 2021

The trading relationship between the US and China was one of the dominant themes of the Trump presidency, forcing the rest of the world to pick a team. At the start of a new administration we take a deep dive into how, if at all, the situation could change under Biden. The first part looked at the prospects for turning back the clock and the second analysed the consequences of a further deterioration in the relationship. This third part assesses the likelihood of a happy compromise between those two extreme positions.

During the early stages of the pandemic Philosopher John Gray wrote a polemic against the dominant global economic model of recent decades in which he declared, “The era of peak globalisation is over. An economic system that relied on worldwide production and long supply chains is morphing into one that will be less interconnected. … A more fragmented world is coming into being that in some ways may be more resilient.” Referring to the pandemic experience, Gray said “a situation in which so many of the world’s essential medical supplies originate in China – or any other single country – will not be tolerated. Production in these and other sensitive areas will be re-shored as a matter of national security.”

Meanwhile, he also conceded that it would be impractical to go all the way back to complete isolated local economies. “This does not mean a shift to small-scale localism. Human numbers are too large for local self-sufficiency to be viable, and most of humankind is not willing to return to the small, closed communities of a more distant past,” Gray wrote.

Our analysis of the rivalry between Corporate America and China Inc. in the technology and telecoms domains sits well with Mr Gray’s predication. The most likely future relationship between the two superpowers will neither go back to the hyper-globalised world nor revert to the earlier model of business conducted on national level entirely insulated from one another. Instead, it will be somewhere in between, a half-way house, or, “the third way” (a term borrowed from Anthony Giddens, now Lord Giddens, the sociologist who was the brain behind Tony Blair’s “New Labour”).

A number of forces are pulling and pushing the relationship between the US and China in general, and its impact on the technology and communications sectors in particular, to different positions. It is the interaction of these forces that will determine where the Biden-Xi house will be built.

There are plenty of forces seeking to “normalise” the relationship, that is to rewind the last four years and more or less go back to the global division of labour. As seen earlier in this analysis, this arrangement has served China better than probably any other country in the world. So there is no surprise that China would pressure the Biden administration towards this direction. Joining this call will be the leading American enterprises, in particular those in Wall Street and Silicon Valley, who have also benefited from the globalist agenda of the recent decades.

There are also forces from outside of the two countries that push for a more collaborative approach towards China. Probably the most vocal modern-day incarnation of Clinton’s “genie theory” is Angela Merkel, the outgoing German Chancellor. Whether she is a true believer in what she publicly says about “engage to change”, or she is simply using it as an outfit to minimise negative sentiment among her European colleagues while promoting German export, is anyone’s guess. The Financial Times calls her EU’s “mercantilist-in-chief” after she played a leading role in hastening the passage of the “EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment” (CAI) before the end of Germany’s presidency of the EU Commission at the end of last year.

The German media outlet WirtschaftsWoche reported, citing its EU sources, that side deals between Germany and China and France and China were also signed, as “rewards” for Merkel’s and the French president Emmanuel Macron’s hard work to make CAI happen. The content of the side deals was kept secret, but WirtschaftsWoche’s insiders in Brussels told the publication that the German deal could see China granting a mobile licence to Deutsche Telekom. As a background, China promised to phase out the protection of its domestic telecoms market within ten years after it was admitted to the WTO in 2001. The French side deal is said to be related to closer cooperation with Airbus. CAI, the full text of which has still yet to be made public, is still subject to the ratification by the European Parliament.

These forces in favour of globalisation did not suddenly appear when the Biden administration came to power. The corporate lobbying in America for continued unbridled trade with China was always a strong voice during the Trump administration (admittedly the lobbying didn’t have to work too hard before Trump came to office). Outside of the US, Xi came to power in 2013 and Angela Merkel has been in the Chancellery for more than 15 years. However, all these factors combined had not prevented the Trump administration from pursuing a hard-line approach towards China to deny the world’s manufacturing centre access to American technologies.

Nor did forces pulling towards independence from the globalised ecosystem start with Trump. On the China side there has always been a desire to own the cutting-edge technologies, and the state has long been investing generously to develop “home grown” solutions to close gaps with the western countries, especially in microelectronics. Such largess would inevitably induce abuse. In one of the most notorious scandals, a scientist in Shanghai claimed to have achieved a breakthrough in signal processing chips to be used in mobile devices, only to be found out to have filed off the Motorola logo on the product and printed his own brand in its place. That was in 2003.

The measures on the American side to rid itself of reliance on supply chains controlled by China got more serious from the second year of Trump’s presidency. Any attempt to consider how the Biden administration will take the rivalry between the US and China must consider not only the directions but also the velocities of the forces in play.

While the voices calling for a return to globalisation have got stronger over the past four years, as a reaction to Trump’s actions in the opposite direction, so do forces for distancing America from China, and to prevent Chinese companies from both accessing American markets and American technologies. Less than one month into the first 100 days of the Biden presidency, the first signs are showing the new administration has no interest in U-turning its predecessor’s overall policy position towards China. If anything, there looks to be strong indications that Trump’s China policies will largely continue under Biden, with some necessary tinkering nonetheless.

Among the first executive orders President Biden signed was one to toughen rules on government purchase to “Buy American” goods and services. While the policy is mostly symbolic due to the small proportion of federal agency procurement in the total economy and the already small proportion of foreign imports in the business, it does send a signal that Trump’s “America First” mantra will be carried forward, albeit under a new brand.

Two of the new administration’s most important nominations, the Secretary of State and the Secretary of Commerce, both went to candidates who believed the US should be tough on China. Antony Blinken, the Secretary of State, said that he agreed with Mike Pompeo, his Republican predecessor, on the definition of the nature of China’s treatment of its Muslim population in Xinjiang. According to his account, he told China’s top diplomat in their first phone call that “the US will defend our national interests, stand up for our democratic values, and hold Beijing accountable for its abuses of the international system.”

Gina Raimondo, Mr Biden’s choice for the Commerce Secretary’s job (yet to be confirmed by the Senate), promised that she would adopt a tough line against trade and technology threats from China. She would “use the full tool kit at my disposal…to protect Americans and our network from Chinese interference or any kind of backdoor influence into our network,” she told the Senate, despite falling just short of explicitly confirming that she would keep Huawei on the entity list. In a latest development, those in the Senate that are more hawkish towards China are working to secure a candidate with similar views to lead the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) in the Commerce Department, to sustain the pressure on technology exports to China.

Such hard-line stance against China shared across the aisle in Congress has become obvious over the increasingly polarised second half of Trump’s presidency. Standing up to China became one of the very few, if not the only, political agendas that could win and have won bipartisan support.

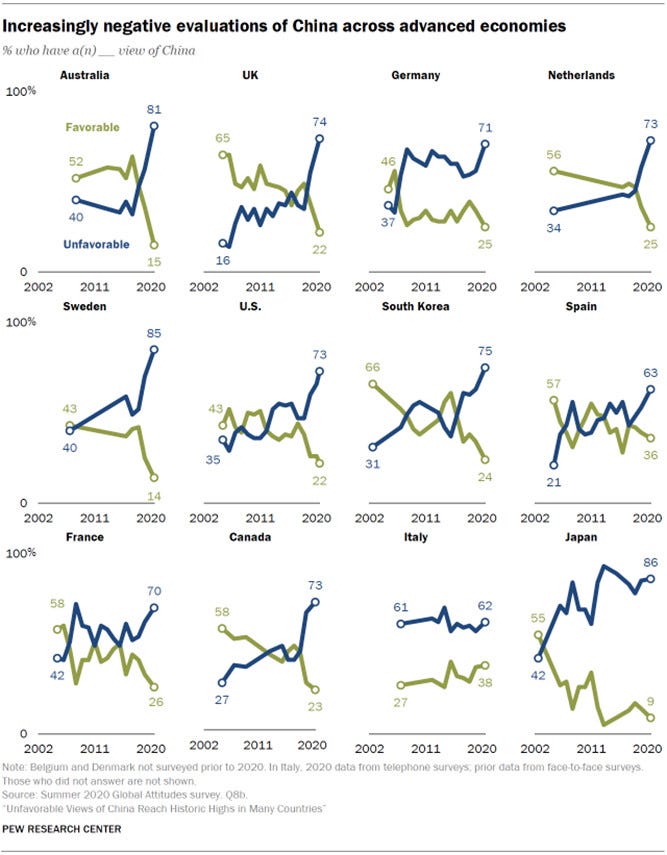

Such bipartisan consensus is a reflection of the new national consensus, and the sentiment is not only restricted to the Americans. Late last year Pew Research Center found China was viewed unfavourably in almost all the developed countries. In some countries the change from favourable to unfavourable views took place within a couple of years (Australia, Canada, the UK) while in other countries the views simply got from bad to worse (Sweden, Germany, the US). China’s handling of the pandemic has hurt its image even further.

On balance we believe the forces pressing for decoupling are stronger than those for more globalising, which would take Biden’s halfway house to three quarters on the road between the two extremes, closer to Trump Tower than to Davos.

******

You can read the fourth and final part of this report here.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

_1.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=800&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)