LTE pricing is changing fast as the market matures. But while some operators are looking to employ elegant new charging models that draw on the sophistication LTE enables, others are still duking it out with least-cost options.

June 22, 2014

Mobile telephony was a premium product for many years; the preserve of wealthy consumers and company-sponsored executives. Penetration only began to skyrocket with the introduction of competition and the ensuing drop in pricing.

That boom in customer numbers translated into success and wealth for the generation of operator executives that engineered it. But competition has continued to intensify, regulation has compounded the pressure and the leaders of today’s operators face a different kind of challenge; keeping prices at levels that are sustainable to their businesses.

Much in the industry is in a process of acceleration. LTE, we are often reminded, has been deployed more quickly than any of its network technology predecessors, is being adopted more quickly and, of course, delivers data far faster. Less appealingly for operators, more rapid uptake of LTE will likely bring with it an acceleration in the erosion of price premiums.

A survey of 50 LTE operators worldwide carried out by UK-based telephony pricing specialist Tariff Consultancy Ltd (TCL), found that 74 per cent of them launched LTE at some kind of premium to existing services. But the fact that more than a quarter opted not to shows just how difficult it is for operators today to link improved performance to increased value in the mind of the end user. And if one operator in a market opts not to raise its price for LTE, the others will have little choice but to follow suit—sooner, rather than later.

Often the disruptive players with the most market share to gain are the most likely to opt for lower prices. Three UK famously announced that it would not attach a price premium to LTE services a full ten months before it actually made LTE available to its customers. The timing of this announcement may well have been motivated by the firm’s need to make itself heard on LTE in the UK at a point when other operators were stealing a march on it in terms of deployment—but it also set off a countdown clock for premium pricing.

Perhaps the most high profile disruptor in the mobile industry in recent years has been Iliad-owned Free, in France. The operator has jolted the French market with its ruthless approach to pricing, and played no small part in forcing a restructuring of the market, the full extent of which is almost certainly not yet visible. The latest estimates for French subscriber numbers from Informa’s World Cellular Information Service Plus show Free having taken third place from Bouygues in WCDMA subscriptions, with 20.5 per cent of the 3G market at the end of the first quarter this year. In LTE, Free has 14.4 per cent.

“In the case of Free Mobile, the introduction of 4G LTE services at the same tariff as 3G HSPA has meant that other French operators have revised their tariffs to follow suit,” says Margrit Sessions, founder of TCL. “So although Orange, Bouygues and SFR did launch at a price premium initially, the price premium was reduced after Free Mobile’s disruptive initiative.”

The 2nd annual LTE Voice Summit is taking place on October 7th-8th 2014 at the Royal Garden Hotel, London. Click here NOW to download a brochure.

In January this year, the MVNO operated by UK supermarket giant Tesco on the O2 network, quietly announced that it was abandoning its attempt to make LTE a premium-priced service. In another illustration of how difficult the strategy is to maintain, Tesco revealed that the small surcharge it had attached to its LTE service—£2.50/month—was being rolled back. The firm had launched LTE only three months previously, with the new pricing described by chief marketing officer Simon Groves as “a great value price”.

Nonetheless some operators are using LTE to drive innovation in the way that they price and sell services, with some specialists in the sector suggesting that differentiated pricing strategies that take advantage of the inherent capabilities of LTE networks might well be the only viable response to the kind of race-to-the-bottom price competition so often bemoaned by CEOs in financial results statements.

Of course LTE can only continue to command a premium while it remains fundamentally a niche product. Once the wider market is being targeted, different strategies are needed to coax lower-spending customers onto the new service. In this area some tried and trusted strategies mingle with newer, more innovative ideas.

First and most obvious, operators have to draw attention to price cuts. At the time of writing, and by way of example, the T-Mobile Netherlands website is promoting a SIM-only LTE offer that gives users 2GB of data and 300 minutes. The price for the deal has been cut by more than 40 per cent, from €38 to €22.

Another familiar strategy, currently visible on the EE website in the UK, is to offer service for free at an introductory level in the hope that users will become attached to the service and begin to pay for it. This is particularly popular at the lower end of the market. EE is currently offering an LTE SIM-only deal that comes with 50MB of data pre-loaded—an allowance that will soon be drained. Once this data has been consumed, users can activite a further free 10GB allowance which they must use within 90 days of activation. Once this second allowance has expired, users must top up to regain data access.

But as well as bringing down prices, operators are also bringing down data allowances, says Martin Morgan, director of marketing at billing and charging software provider Openet. And this has had an interesting effect. “Prices for LTE have been coming down while speed has been going up. Some operators are now offering 500MB packages, some even 200MB for the initial package. But as you lower the entry level volmes, because the speed has increased, customers are going to hit their limits much earlier.”

This provides operators with a clear opportunity to either migrate users to larger and more expensive data plans, or to sell smaller add-ons to see users through to the beginning of their next cycle.

Research conducted by Informa Telecoms & Media and Mobidia has looked in detail at the extent to which users consume the data made available to them in their bundles. Using data from users of Mobidia’s My Data Manager application, the research covered tens of thousands of 3G and 4G Android smartphone users in ten markets; South Korea, Japan, USA, Canada, Germany, UK, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Russia and Brazil.

The results, and what they mean for operators, are mixed. Data compiled by Mobidia showed that more than half of customers used less than 50 per cent of their monthly data allowance in January 2013, across all data-plan sizes.

As might be expected, the percentage of subscribers using less than half their allowance was higher for those with larger allowances. While 55 per cent of 4G smartphone users with plans between 1 – 500MB in size used less than half of their allowance, the number rose to 69 per cent for users with allowances in excess of 5GB. This may seem at first to be a positive for operators; like the owners of gyms the world over, they are being paid for a resource that their customers are not expoliting fully. But report author Mike Roberts warned that, as users gain more insight into their own usage patterns, they may well seek to downgrade, and spend less.

More promisingly for operators, the number of users exceeding their data allowance increased during the course of 2013, across 3G and 4G and across all plan sizes. Furthermore, as Roberts wrote: “The share of users exceeding their plan limit was higher for 4G smartphones than for 3G smartphones…. Country level data for 4G smarpthone users in December 2013 shows that the share of users exceeding their monthly plan limits increases as 4G penetration increases.”

Of the markets featured in the study, South Korea had the highest instance of this phenomenon, with 31 per cent of users across all plan sizes exceeding their limit, the research found. In Japan the figure was 21 per cent, in the US 17 per cent, in Canada and Germany 15 per cent and, in the UK, 11 per cent.

“We’re only going to see more of these real-time add-ons being sold,” says Openet’s Morgan, “as operators reduce the size of their entry level packages and their prices while increasing network speed.”

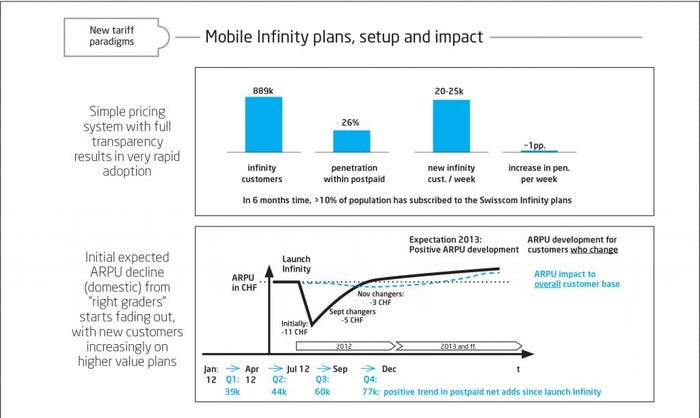

Increases in speed capabilities are also being leveraged by some operators seeking to maintain some kind of premium peformance association for LTE. Swisscom introduced its “Natel Infinity” mobile data tariffs in June 2012, in a bid to make the unlimited plan—something that has come increasingly under fire since it was first used to stimulate mobile data uptake—easier for the consumer to understand and more positive for its bottom line.

The twist with Infinity is that, while user data consumption is not capped, it is charged according to different tiers of service. At launch the tariffs ranged from the XS CHF59/month (€48.33) for speed capped at just 0.2Mbps and all voice and SMS included, to the XL CHF169/month (€138.43) for 100Mbps speeds, all voice and text and substantial roaming and international calling bundles (see slide for full range).

Launching the tariffs, Swisscom said: “Surveys of Swisscom customers have shown that they are unable to visualise megabytes and often do not know how much data they send and receive. As a result, they restrict their usage to avoid extra charges. The new Natel Infinity subscriptions will render this unnecessary, as they will include data traffic. The offerings will be the first to offer a choice of transmission speeds, which are easier for customers to understand. Customers will in future only pay for the speed they require.”

In an analyst presentation delivered in the first half of 2013, Swisscom said that the simple and transparent pricing that the Infinity subscriptions offered had resulted in “very rapid adoption” (see slides on this and previous pages). While there was an initial drop in ARPU during the first six months, the firm said—which was expected as a result of some users moving to a lower-cost experience that met their needs—this tailed off fairly rapidly. New customers, said Swisscom, were “increasingly on higher value plans”.

Simple Pricing Equals Happy Customer

Switzerland is a comparatively expensive country but Swisscom’s experience shows that it is possible to maintain a premium for service. The tariffs at either end of the range may well have limited appeal but the mid-range offers allow users to choose a package based on something they can understand, not least because it is familiar from the world of fixed broadband pricing.

Working along similar lines but distinguishing instead between prepaid and postpaid is Swedish operator Telia. Users of the firm’s SIM-only 4G ‘Telia Refill Startpaket’ can only have LTE service at speeds up to 20Mbps, according to the firm’s website, accessed in May. If higher speeds are sought then users must upgrade the type of contract they have with the operator.

In the same presentation in which Swisscom discussed its Infinity plans, the operator observed that its revenue from specific services (fixed and mobile voice, text, etc) had dropped substantially, thanks to internet and OTT based alternatives. “Pre-internet,” the firm said, 75 per cent of revenue was tied to usage of a specific service. That had fallen to 36 per cent at the time of the presentation. “The only thing a customer needs is (multiple or bundled) high quality access subscriptions,” Swisscom said. Operators have “no choice,” it added, “but to prepare for the day when there will ne no usage based fees left.”

Others argue that service-based pricing remains crucial—it’s just the services on which operators are focused that need to change. “It will be better for everyone if we can get to amore segmented pricing environment,” says Andy Tiller, VP for marketing at Chinese BSS vendor »

AsiaInfo-Linkage. “Instead of having a data bundle people should be paying for the services they want. At that level if a parent wants to allow their kids to watch only a certain amount of YouTube, or restrict some services and not others, they’ll be able to.”

Tiller’s suggestion derives from the same observation as Swisscom’s decision to go for speed-based, unlimited plans—namely the fact that users don’t understand Megabytes. And bids to familiarise users with the concept of consuming specific services rather than is already underway. In the UK EE has a video on demand service offering cheap films streamed or downloaded over its LTE network, for which it is currently waiving the data charges.

Again users are being encouraged to try something for free or low cost that, subsequently no doubt, they will be asked to pay for. But it would seem likely that, when the subsidy is removed at the beginning of 2015, it will be the films that users will pay for—and not the data.

And if operators don’t want to subsidise usage themselves, then perhaps they can find a partner to do it for them. US operator AT&T launched a sponsored data offering in January this year that enables “eligible 4G customers to enjoy mobile content and apps…without impacting their monthly wireless data plan.” The move met with a range of responses, including some net-neutrality sabre-rattling from US authorities.

But Informa analyst Julio Puschel suggested in the wake of the launch that the service would have most benefit as a new advertising model. “Initially, some market observers assumed that the main aim of the model was to enable AT&T to recoup extra revenue from OTT services by introducing a way to charge them directly,” Puschel said. “But Informa believes that its major potential instead lies in offering a new advertising model, in which companies can offer data-heavy ad content that users can view without incurring data charges. For example, Netflix could use sponsored data not to subsidise internet costs for users viewing an entire movie, but to turn mobile into an additional advertising medium by offering free-to-view trailers to mobile customers.” Crucially, however, such a strategy would be likely to encourage users to start paying for content when the consumption experience proves satisfying.

Perhaps the biggest news in mobile pricing to come out of the US in recent years has been the success enjoyed by the market’s operators, AT&T and Verizon, perhaps in particular, with shared data plans. Reporting its first quarter financials in April, AT&T revealed that its Mobile Share plans, which allow subscribers to connect multiple self-owned devices, or multiple family-owned devices to a single bucket of access, now accounted for almost 33 million connections—or 45 per cent of the firm’s postpaid subscribers.

The number of shared plans tripled year on year to 11.3 million, with an average of three devices per account, the firm said. Morevover, uptake for the higher data-rate plans was encouraging. AT&T said that at the end of the first quarter this year, 46 per cent of Mobile Share accounts were on 10GB or higher allowances, up from 28 per cent at the same point in 2013.

Mobile pricing has always been convoluted. Even when voice and text were the only services available, the operator community was renowned for the often impenetrable complexity of its tariff structures. Today the variety of data and LTE pricing strategies reflects something more positive than the deliberate customer bamboozling that was commonly believed to be at the heart of operators’ tariff plans of years past. Because today operators are trying a range of different models in a bid to learn which ones will be, on the one hand, easy for consumers to understand and, on the other, beneficial to their business at a time of great competition and regulatory pressure.

There are, says TCL’s Margrit Sessions, no dominant trends in LTE pricing, which reflects the exploratory nature of the exercise today. Not least this is because one operator is very different from the next. Those with full multiplay offerings, for example, are increasingly positioning the bundle as the differentiator, rather than specific mobile pricing. And while some are looking to protect revenues with innovation and value creation, others will doubtless continue to target customers with cut-price offerings.

“Part of the answer to that sort of competition is to provide innovative pricing that your competitors can’t copy,” says AsiaInfo’s Andy Tiller. “One of the things that’s holding some operators back is the legacy IT infrastrcuture that’s in place. That might be part of the reason why prices are being kept the same with the move to 4G, certainly in markets like France.”

With LTE, operators now have networks in place that make greater elegance and sophistication in pricing possible. They can deliver dynamic policy and bearer set up, making it easier to provide services like turbo boosts. And they are now able, crucially, to check whether or not the intended quality of experience was actually delivered. And operators are starting to separate into those that are exploiting such sophistication and those that are not.

Infinity Is Expected To Have A Positive Effect On Arpu In The Long Term

Read more about:

DiscussionAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

_1.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=800&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)