The surge in mobile data and broadband traffic in advanced markets over the last couple of years is something of a double-edged sword. While it has finally validated carriers' long-held strategic thinking, it has exposed gaps in their network performance.

March 3, 2010

The surge in mobile data and broadband traffic in advanced markets over the last couple of years is something of a double-edged sword. While it has finally validated carriers’ long-held strategic thinking, it has exposed gaps in their network performance.

The world of popular storytelling is full of tales that caution the reader to be careful what they wish for. After all, they might just get it. Since the 3G auctions began a decade ago amid a cycle of hype that, ten years on, looks like a kind of mass hysteria, the wish of mobile operators in the most advanced markets has been for sufficient uptake of mobile data services to justify the enthusiasm with which they snapped up 3G licences.

It’s been a long time coming and, now that it’s here, it is proving to be something of a mixed blessing. While the arrival of genuine mobile broadband capability is a cause for celebration, some carriers have been caught short by the sheer scale of uptake. Victims of their own marketing push-offering ‘unlimited’ data usage for relatively low subscription charges-and the unforeseeable impact on users of the iPhone and the devices it has subsequently influenced, carriers have been overtaken by events.

High profile headlines have seen US carrier and iPhone pioneer AT&T castigated for failing to deliver a sufficiently robust network to cope with the handset’s uptake, and UK player O2 making public apologies for similar shortcomings.

Figures from Informa Telecoms & Media show that total mobile traffic in 2008 measured 1.1 exabytes (trillion megabytes) worldwide. This is forecast to grow to 2.5EB in 2010 and 18EB in 2014. While some of that will be traditional, circuit-switched voice traffic, mobile broadband is set to explode, surpassing 14EB during 2014.

By the end of 2010, mobile broadband subscribers worldwide will number 450 million, which will represent a 45 per cent share of the global broadband market. In 2011, though, the mobile broadband market will overtake the fixed segment, growing to near 670 million subscribers and a 51.8 per cent market share. Despite a healthy CAGR of 12 per cent between 2008 and 2013, Informa says, the fixed market’s share of global broadband subscribers will drop by half over the forecast period from 70 per cent to 35 per cent.

Carriers have won what they wished for, and the problem of provisioning capacity for the data boom is clearly not going to disappear any time soon. Mobile users vote with their feet and poor network performance is something to which they assign great value. Application performance specialist Compuware recently conducted a survey of senior executives at 22 mobile broadband operators from around the world in a bid to gauge their visibility of customer experience and satisfaction. The results, according to Jerry Witcowicz, product manager for Compuware’s Vantage for Mobile solution, make for a sobering read.

“All of the executives we interviewed said that experiencing a poor performance in data service is the top reason for their customers to churn,” Witcowicz says. One interviewee revealed that, “when we introduced the iPhone our traffic spiked by 30 per cent and the capacity did not keep up.” Another revealed: “We expect the network traffic to increase 50 times in the next few years.”

The two mobile broadband segments- dongle/embedded laptop (portable) and smartphone (mobile)-are each problematic. Portable usage accounts, and will continue to account, for the overwhelming majority of mobile broadband usage. Informa figures for global mobile network traffic show portable usage at 1EB in 2010, almost 90 per cent of traffic. By 2014 this will have grown to 14EB, representing 93 per cent of traffic.

But this does not mean that portable traffic represents the only challenge. UK carrier O2 has been deliberately slow into the dongle market but has been hard hit by uptake of the iPhone. And mobile broadband-capable handsets are going to grow in number enormously over the next four years as technology gets pushed further down device ranges.

According to Dave Nowicki, vice president for marketing and product management at US network and femtocell provider Airvana, smartphones have their own particular issues. Studies conducted by Airvana on EVDO networks in the US and Asia, he says, have found that smartphones place a far higher signalling burden on the network than dongles and embedded laptops-a problem he says has just as much relevance to carriers using 3GPP standards.

“We found that there was this amazing acceleration in signalling traffic. On measuring it what we noticed was that while a dongle or data card was using 25 times more data than a smartphone, the signalling ratio was only three to one,” he says. “Which means that, for every bit it sends, the smartphone is pumping out eight times more signalling traffic.” Nowicki argues that this requires a shift in the way networks are dimensioned, with carriers needing more radio network controllers. “It’s not so much a spectral efficiency issue,” he says, “it’s more about the cost per megabyte increasing. The cost to deliver a megabyte to somebody is no longer defined just by how many megabytes you’re sending. It’s no longer a common number, it’s now influenced by the mix of your traffic.”

It’s almost a tradition in this industry to look to the dawn of the next major technological era as the answer to everyone’s problems. But in these straitened times many operators have conceded that LTE, the champion of the fourth generation, may be slower to arrive than originally anticipated. So what can carriers do?

A variety of options are open to them, some network based and some more strategic than technical. Perhaps the most obvious solution is simply to put in more cell sites. It’s the kind of response that enables an operator to show contrition to disgruntled users as well as a willingness to roll up its sleeves and solve the problem.

At the end of 2009, O2 UK made just such an announcement in the wake of its iPhoneinduced network issues. The firm promised to build out 1,500 new network sites in 2010, with 200 planned for London, where the iPhone (along with critics from the press and analyst communities) is present in the greatest concentration. The firm said its investment would run to hundreds of millions of pounds, and followed a £500m payout over the previous two years in order to meet increased demand for data.

Such a response has its detractors, though. John Spindler, vice president of product management at ADC argues that traditional behaviours require a rethink. “Things have to change in the way that carriers look at the network architectures and network topologies,” he says. “The old days of throwing up cell towers and doing what we used to refer to as ‘spray and pray’ just isn’t going to be adequate. It’s becoming impossible.” Even those who back the effectiveness of such a strategy concede that there are obstacles. Land is a finite resource and, in the kind of dense, urban areas in which capacity boosts are most sorely required to accommodate data surges, sites are at a particular premium. Such build-outs are also arguably the most costly form of improvement upon which an operator can embark.

“It’s an irony particular to the mobile data boom that wireless carriers, for so long motivated by drawing business away from the fixed line, are now scrambling to dump their own traffic back onto it wherever it’s available…”

But, says Mike Roberts, senior analyst at Informa Telecoms & Media, the cost need not necessarily be prohibitive. “When you get down to the network itself, it can just be ten or 15 per cent of your base stations that are generating the vast majority of your traffic,” he says. “So it might not be a massive investment programme that you’ll need to undertake to add capacity to the base stations that are overloaded. From that point of view it can be a manageable problem,” he says. Roberts’ assessment of geographical load differentials chimes with a statement made late in 2009 by Ralph de la Vega, chief executive at US carrier AT&T. Q309 saw record activations of the iPhone for AT&T but, said de la Vega, just three per cent of his customers were generating 40 per cent of his data traffic.

But some argue that although major network deployments may offer a solid capacity solution, the time involved in making them happen lessens their effectiveness in dealing with a problem that requires an immediate solution. Capacity in other forms is already in place, they say, and can be used to alleviate the pressure more promptly.

These people are proponents of offload strategies, using either wifi or femtocell technologies as a release valve for congested mobile data networks. It’s an irony particular to the mobile data boom that wireless carriers, for so long motivated by drawing business away from the fixed line, are now scrambling to dump their own traffic back onto it wherever it’s available.

“Offloading to wifi is great for us and great for the customer,” says Matthew Key, CEO of Telefónica Europe (read the full, exclusive interview with Key on p18). “The customer gets a better experience and it takes the traf- fic off of our network,” he adds, in the kind of statement that might almost have been unthinkable from a large cellular carrier just a few years ago.

“We’ve got agreements with The Cloud and BT in the UK but we’re also going through an educational process with users about how to make use of wifi in their home. The vast majority of people now have broadband in their home, with a wireless router,” he says.

Key’s last point highlights the relevance of offload strategies in a world where a great deal of mobile broadband usage is happening in the home. Airvana’s research, says Dave Nowicki, shows that the peak time for mobile data traffic is the evening. Given that that peak traffic remains on the one cell, and that most people are home in the evenings, that traffic must be coming from the home, he says. The total share of home-based mobile broadband could be as high as 50 per cent, he adds.

Most laptops today ship with wifi embedded and most smartphones, too. As Stephen Rayment, chief technical officer at Belair Networks, a specialist in wifi offload, argues: “The problem and solution lies in the palm of our hand. More than 1.5 billion wifi chipsets have been shipped to date and we’re looking at one billion run rates in four or five years. Wifi is pervasive and is a very effective way of getting some of that data traffic off the mobile networks.”

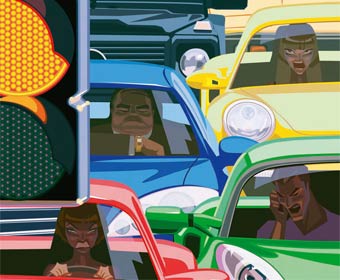

overcrowded

Will Network Overcrowding Cause The User Experience To Deteriorate?

Rayment argues that wifi makes sense for wide area capacity relief for two reasons likely to prick up the ears of any carrier with a capacity issue; the ease and speed with which it can be deployed, and the cost. Historically the firm’s customers have been owners of large venues like sports arenas and shopping complexes, as well as fixed broadband players looking to add nomadic wireless access to their portfolio as a sweetener. Rayment says wireless carrier deals are in the offing for the first half of this year. “The big advantage for mobile carriers is that they can deploy this offload at anywhere from one third to one tenth the cost of deploying wholesale upgrades to their mobile network,” he says. “You can deploy wifi in a targeted fashion; where the 3G carriers’ subscribers are congregating and where the cell towers are glowing red hot. Plus the devices are already here. We all know LTE is coming but we don’t have to wait for it.” Furthermore, he says, the wifi networks can be plugged into a carrier’s network operations centre, and can be managed using existing tools.

Not everyone is convinced, though. “The thing about wifi,” says ADC’s John Spindler, “is that it was never designed for wide area use. From the attempts that we’ve seen to put in metropolitan wifi networks we’ve seen that it doesn’t work. Most have failed miserably. It’s really designed for smaller coverage areas and has a limited number of channels on the access points that you can actually deploy. It’s good as a hotpsot technology for coffee shops, but not for wide area. Plus it operates in unlicensed spectrum so you get more interference.”

Rayment concedes that, three or four years ago, it was all but impossible to take a wifi offload solution to a mobile carrier “without being ridiculed”. Central to carriers’ objections, he ways, was the problem of operating in unlicensed spectrum; something he says has now been overcome. “I think they’re beginning to see that you can do some pretty good networks with unlicensed spectrum. Plus there are so many pressures on the mobile carriers-the loads on the networks are driving them to do this.”

The offload alternative to wifi in the home is the femtocell. Having occupied the ‘next big thing’ slot on the mobile networks agenda for some time, femtocells are now starting to gain traction. SFR, Vodafone, Sprint and AT&T are just some of the operators to have made high profile moves in the space. But to date most carrier uptake has been driven by coverage issues in a bid to address indoor signal performance, says Dave Nowicki of Airvana, supplier to Sprint.

“Coverage is the pain spot that everyone really understands at the moment,” he says. “But people are realising now that there’s a capacity pain point as well, and I expect that capacity femto deployments will be the next phase.”

But femtocells, like all solutions, generate issues of their own. Some detractors suggest that femtocells could create problems with interference, and that users on the macro network could experience performance problems when in proximity to a femtocell. But it seems the most serious sticking points could be commercial rather than technical.

The last thing cellular carriers need is another expensive device to subsidise into consumers, and asking subscribers to pay out for something to improve a service for which they are already paying is a difficult proposition to work. Vodafone, which was the first European carrier to launch femtocells in July 2009, revised its offering in January 2010, giving added weight to the view that femtocells are a tough sell.

The first move was to change the name of the offering from Vodafone Access Gateway- a network-based name if ever there was one-to Vodafone Sure Signal. Prices were cut with the rebrand and now the product costs £50 in a one off charge, or £5/month for 12 months on price plans of £25 or more. If customers spend less than £25/month, the price is £120 in a one off cost, or £5/month for 24 months.

While he agrees that femtocells are a solid proposition for domestic usage, ADC’s John Spindler believes that, like wifi, they are not suitable for use as a capacity enhancement in the wide area. ADC favours distributed antenna systems that use fibre to connect smaller cells to the macro base station, generating what Spindler claims is more efficient use of spectrum and a reduction in practical hassles.

“When you aggregate a BSS location like this, you’re talking about eliminating a lot of the cost of real estate acquisition, eliminating a lot of the time involved, lowering power and HVAC requirements and enabling easier maintenance because all the upgrades are done at the central BSS location,” he says.

What all of these solutions have in common is that they are designed to ease the strain on the radio access network. But the RAN is not the only part of the network that requires attention. “Backhaul is a huge focus for all operators,” says Bradley Mead, vice president for services and multimedia at Ericsson, whose responsibilities include managing the network owned by T-Mobile and 3UK’s MBNL joint venture.

“You have to get enough coverage and capacity into the RAN to be able to deliver the service, but then the bottleneck moves up to the backhaul. Because if the backhaul’s not there to support the RAN, there’ll be a big problem.”

Lance Hiley, vice president for market strategy at microwave backhaul specialist Cambridge Broadband Networks, takes a similar view. Backhaul provisioning is complicated by the same issues as RAN provisioning, namely the difficulty, involved in predicting where the traffic surges are going to appear, and providing enough capacity to cope with them.

The ideal solution for backhaul, Hiley concedes, is fibre, which has limitations far beyond those of the network elements it is being used to connect. The problem, as always, is cost. The answer, says Hiley, is microwave.

“You probably have enough credit on your Mastercard to buy a point-to-point microwave link that could backhaul 100Mbps over 2km,” he says. “But you’d probably have to take out a second mortgage on your house if you wanted to do the same thing with fibre. In Western Europe we have fewer than 30 per cent of cell sites connected by fibre. If you think about how many cell sites there are in Western Europe and what it would take to connect the remaining 70 per cent by fibre. It would put the UK trade deficit in the shade.”

The enthusiasm for microwave is driving saturation of the spectrum that’s reserved for backhaul, he says, which is why point to multipoint backhaul architectures are coming increasingly to the fore. “With point to multipoint you can deliver a much better quality of service because you’re dynamically allocating resources, while at the same time making the most efficient use of spectrum resources,” he says.

The reality is that most carriers will use a range of technical methods to help them deal with the boom in mobile data traffic. In the meantime, the issue of tiered service is rearing its head. Some carriers-Vodafone Portugal is one-are putting software into their networks that throttles back the speed available to subscribers who have exceeded their fair usage caps. Others, AT&T included, are introducing price hikes to dissuade customers from excessive usage.

It’s a divisive strategy. ADC’s John Spindler describes price caps as “a crazy business model.” Compuware’s Jerry Witcowicz, meanwhile, says that “what we hear from customers is that the unlimited usage offer is a losing proposition. You can’t afford to offer unlimited usage, operators have to have caps.”

Telefónica Europe CEO Matthew Key says he is undecided, and that a policy is being thrashed out within the group at the moment. “How many industry that are relatively capital intensive can live with a model that says ‘pay one fee and it doesn’t matter how much you consume’? People who are using multiple gigabytes each month are paying the same as somebody who’s using one megabyte. The key is to get a balance between the two, and that’s a live strategic debate for us at the moment.”

And, one suspects, for many other carriers watching the sudden boom in mobile data usage.

Read more about:

DiscussionAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

_1.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=800&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)