Microsoft suggests FCC is telling Porky Pai’s

New Microsoft research suggests the digital divide in the US is much more prominent than any of the politicians, who are supposedly fixing the problem, would let you believe.

December 6, 2018

New Microsoft research suggests the digital divide in the US is much more prominent than any of the politicians, who are supposedly fixing the problem, would let you believe.

The digital divide is one of the most active political ping-pong balls in recent years, with US politicians seemingly using the desirability of bufferless cat videos to gain support in some of the country’s poorest communities. If you believe what the FCC has been telling the media, this disparity has been getting smaller, though it is still large.

The Microsoft research suggests very little or no progress is being made and the FCC is misleading US citizens.

Looking at the statistics, the FCC claims the digital divide currently stands at 22 million across the US. The threshold seems to be what many would consider basic broadband speeds. With so much of the world become digitized it is critical every person is not only granted access to new opportunities, but also allowed to continue using basic services (such as banking) which are increasingly moving into the digital world.

Looking at the Microsoft research, the team is suggesting around half of US citizens, 162 million, are not using the internet at broadband speeds. The difference between the two numbers is quite staggering, and while it does question to competence at the FCC, the answer might be a bit simpler; it’s all a game of politics.

When looking at the figures it is important to understand the FCC estimates on the digital divide are based on those individuals who can theoretically access the internet. There might be various other reasons why they do not, price for example, but these factors do not seem to be considered. Why you might ask? We suspect it is not politically convenient.

If you look at the last US election campaign trail, the idea of the digital divide was a hot topic. Both President Trump and the Democrat candidate Hillary Clinton suggested tackling the issue would be a high priority for their administrations, buying favour in communities which could (and eventually did) turn the tide in the election.

The FCC is a body which is funded via the pockets of the tax payer, therefore it does have to demonstrate it is fulfilling the objectives set out before it. Holding telcos accountable to theoretically offering broadband access is a much simpler job than ensuring these business price it at a cost which would be deemed accessible.

The Microsoft research is based on those who are using the internet at speeds which would be deemed relevant to broadband. Slow broadband could be deemed as bad a no broadband in some cases, with websites timing out or taking so long to load little could be achieved. With this in mind, stories about kids making use of McDonalds wifi to do homework start to make sense.

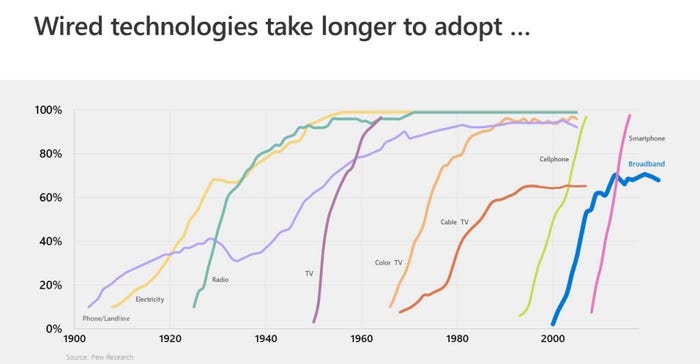

As you can see from the graph below, wired technologies do generally take a lot longer to reach 100%, especially in a country which is as vast and varied as the US, though broadband has been sluggish in recent years.

But before you start to congratulate Microsoft too much, you must take into account its position is also political, or perhaps PR-drowned is more accurate. One of Microsoft’s more prominent CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) initiatives is closing the digital divide. If the problem is much worse than people originally imagined, the corporation coming in to help looks much more glorious.

On both side of the coin you have to take the claims with a pinch of salt. The FCC will continue to make bold statements on progress to ensure favourable light is shed on the Trump administration at a time where the White House will be starting to consider the next election, while Microsoft has a lot to gain commercially through the Airband Initiative, a five-year commitment to bring broadband access to two million unserved US citizens living in rural communities.

Microsoft is not wrong, and we suspect the way it is judging the digital divide is more accurate (usage vs. theoretical accessibility), but it always worth remembering there is always something to gain.

About the Author

You May Also Like

_1.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)