Corporate America vs China Inc: what the Biden years will mean for telecomsCorporate America vs China Inc: what the Biden years will mean for telecoms

With the Biden administration keen to turn back the clock on many policy fronts, it is worth examining what this may mean for the next episode of the USA China rivalry, especially in the technology domains.

February 15, 2021

The trading relationship between the US and China was one of the dominant themes of the Trump presidency, forcing the rest of the world to pick a team. At the start of a new administration we take a deep dive into how, if at all, the situation could change under Biden. This first part analyses the prospects of trying to turn back the clock.

With the Biden administration keen to turn back the clock on many policy fronts, it is worth examining what this may mean for the next episode of the USA China rivalry, especially in the technology domains. This article aims to provide telecoms stakeholders with analysis that they can use to best prepare for the next four years.

After being sworn in Mr Biden dived straight into signing executive orders to revert many of his predecessor’s policies, from re-joining the Paris Climate Accord and the World Health Organisation to repealing the ban on immigration from a group of Muslim-majority countries. The busy executive actions looked to be signalling a full-blown return of the American agenda to the Obama or even Clinton era.

Meanwhile, the signals regarding the Biden administration’s China policy are not yet clear, despite the recognition that China will be one of its biggest challenges. None of Mr Biden’s executive orders so far concern China, at least not directly. If anything, the initial signs are pointing to a continuity from his predecessor’s approach towards China rather than a hard break or a sharp reversal.

The telecoms sector has been caught in the geopolitical theatre played out by the world’s two biggest powers. Even those industry stakeholders not based in either the US or China have been forced to take a position, so long as they have business interest in those markets. Therefore, facing the mixed signals from the early days of America’s new administration, it makes sense for the industry to take a closer look at the likely near future scenarios of this era’s dominant geopolitical tension.

Good ol’ days?

One scenario requires us to go back to the globalisation along the lines of the so-called “Washington Consensus”, a throwback to the Clinton years (the President, not the Secretary of State). It was Bill Clinton who granted China accession to the World Trade Organisation (WTO). He harboured the view that through “constructive engagement”, America and its allies could make China embrace values more in line with those of the western democracies. Clinton famously claimed that economic freedom would lead to wholesale change of the society. “The genie of freedom will not go back into the bottle.”

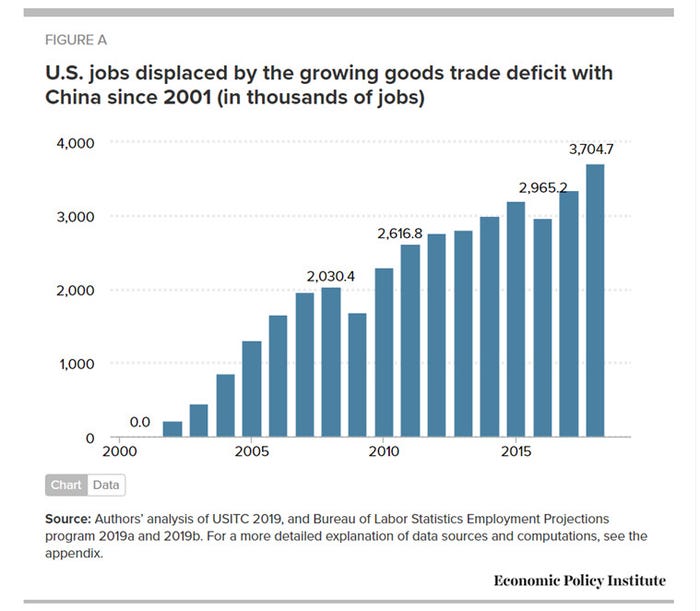

If there ever was such a genie, it had not been in the bottle labelled WTO. On one hand, China has been the single largest beneficiary of the global economic order of the last two decades, doing so largely at the expense of the US. According to an analysis by the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), a Washington D.C.-based thinktank, by the end of 2018 more than 3.7 American jobs have been displaced by trade with China since the latter joined the WTO in 2001. Among them, 2.8 million lost jobs were in the manufacturing sectors, all while China became the world’s manufacturing centre.

On the other hand China, always a party-state since the end of the civil war, has become increasingly authoritarian. If tolerance for political dissent was deemed limited during the Clinton administration, thus “change” was desirable, that change has been made in the opposite direction to what was hoped. The limited tolerance is practically non-existent now. The government and the ruling Communist Party (mandated by the Constitution to “lead” the country indefinitely) have become much more domineering inside the country (and more assertive outside it) since Mr Xi Jinping assumed the supreme leadership in 2013.

It therefore should surprise no one that China would continue to love a globalised trade order while maintaining and upgrading its own governance model, though in a different role. This time around, instead of merely being a rule-taker (despite never sufficiently fulfilling the WTO obligations to open its market, including the telecoms market), China aims to be a rule-maker, to reshape the world in its own image. This is delivered under the slogan “common destiny for mankind”, a brainchild of Mr Xi which has been drummed up through all the official propaganda channels (and the unofficial ones too, voluntarily or not). In essence this means China will want not only to keep its position as the world’s manufacturing centre but also to move upstream to set industry standards and trading terms.

What may be surprising is how many among the corporate America elites are also enthusiasts of going back to the golden age of globalisation without ruffling China’s features. It should be recognised that many of them are true believers in globalisation and its benefits to all. However, a significant number of former and current corporate America members now defending unbridled free trade with China have more captive interest. There are two major groups of this kind.

The first group is comprised of politicians turned lobbyists, hired by American companies to do their bidding in China (and outside of it). As it turns out, to defend their employers’ interest these influential figures often find themselves lobbying on China’s behalf because of these companies’ significant business operations in China. Many examples of this sort of thing are given in The World Turned Upside Down: America, China, and the Struggle for Global Leadership, a recent book by Clyde Prestowitz, President Ronald Reagan’s commerce advisor.

If the American politicians’ “revolving door” practice might raise one or two eyebrows because of its moral ambiguity, their European counterparts have by-passed this stage and adopted a “route one” approach, to use a football analogy. Many of them moved directly to work for China Inc. after leaving their political positions.

A second group are the current crop of corporate America’s top executives, some of them therefore employers of the first group. These companies either already have a stake in the sectors China has opened to competition or are coveting its potential. Thus, they are not only doing everything demanded of them by the Chinese government but also justifying these demands when called in front of the American law-makers. Google has been exposed to have gone a long way to develop a censored search engine to get back to the Chinese market. Both Apple and Google were happy to pull from their application stores an app to track police deployment in Hong Kong when the authorities became irritated.

In a more bizarre twist of events recently (and in the broader China vs Western context), Borje Ekholm, CEO of the Swedish kit maker Ericsson, took on his own government for its decision to ban Huawei from the country’s 5G network building. Whether he did so because he is a true believer of free and fair competition, or because of mercantilist calculation that Ericsson sells much more in China than Huawei can sell in Sweden, or his plea was made under some sort of duress, Mr Ekholm alone knows. To observers, however, the fact that he went the length to make the plea to begin with is a clear sign of how much China has had foreign enterprises in its back pocket.

To look at the globalised world economy from the western perspective, it is efficient but far from resilient. A year ago, when COVID-19 started to ravage country after country, the world suddenly realised the limitations of division of labour on a global scale because the vast majority of personal protective equipment (PPE) was manufactured in China. The Chinese government therefore could (and did) restrict the critical products from being shipped out of the country. It should be noted, however, that this was not too dissimilar to what a number of European Union countries did to each other by closing borders when facing shortage of PPE at the beginning the pandemic, or what the European Union recently attempted to do to the UK when the block found itself lagging far behind the recently departed island state in vaccination rollout.

The Pearl River Delta in southern China, bordering Hong Kong, has evolved into the global manufacturing centre for consumer electronics products. Foxconn, the Taiwanese OEM, has in Shenzhen its largest operation of its global network, and has a critical role to play in the success or failure of companies ranging from Apple to Sony. Both Nokia and Ericsson produce significant proportions of their telecom network equipment in China. This puts many companies’ critical supply chains at the mercy of the local and central governments of China.

So, the globalist model in one shape or another has served China much better than it has served America, which has not only lost out economically but also failed to see meaningful gains on the political or moral fronts as consolation. It is therefore hard to expect the Biden administration pursue a full-blown return to this approach towards China.

******

You can read the second part of this article here.

About the Author

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

_1.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)