Africa gets smart: continent prepares for device revolution

Africa’s mobile market has largely been characterised by demand for low-cost prepaid feature phones. However, this is beginning to change as the cost of technology gradually declines and handset manufacturers operating in Africa are now preparing for a smartphone revolution in the coming years.

January 9, 2014

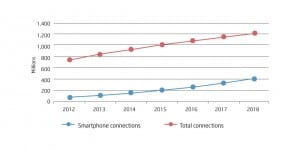

Africa is one of the few regions in the world where growth in both mobile connections and service revenue is expected over the next five years, according to recent research published by Ovum. This reflects the comparatively low penetration and revenue levels, the economic hardship the region has faced in recent years and also the fact that many African markets are somewhat behind the technology adoption curve when it comes to mobile.

Disposable income in most African nations is a fraction of levels seen in markets in Western Europe, North America and certain parts of Asia; 16 counties in Africa had a GDP per capita of $1,000 or less in 2012, according to the CIA World Factbook, and the next 15 wealthiest countries in the region have a GDP per capita of less than $2,000. The 2012 world average GDP per capita stands at $12,700, putting Africa’s economic situation into context.

It is for these reasons that Africa is predominantly a prepaid environment, where most consumers opt for low-priced feature phones. African operators rarely offer handset subsidies, only doing so in the comparatively mature markets of Morocco and South Africa, where there are higher proportions of postpaid users.

Much of the rest of the world has firmly embraced the move to smartphones; around one in every four people worldwide is now a smartphone user, according to figures for July this year from Informa’s WCIS+. By contrast Africa has just 112 million smartphone connections in a 930 million total handset base, putting African smartphone penetration at just 12 per cent—the lowest penetration rate of all the regions in the world. Existing smartphone users are concentrated in the wealthier markets and urban areas; if these are discounted the overall penetration rate would drop further. Meanwhile there are still 100 million Africans who do not have a mobile device at all.

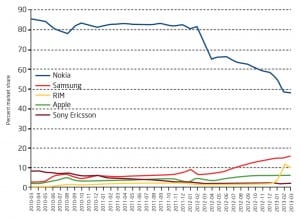

This makes the “first phone” market an important sector in Africa and it is a handset category that has helped Finnish vendor Nokia—which has suffered calamitous market share declines in more advanced markets—climb to a dominant position in the region.

This makes the “first phone” market an important sector in Africa and it is a handset category that has helped Finnish vendor Nokia—which has suffered calamitous market share declines in more advanced markets—climb to a dominant position in the region.

“In Africa, the first mobile phone is likely to be even more basic than today’s average feature phone,” explains Nokia’s head of mobile phones for India, Middle East and Africa (IMEA) Calin Turcanu. “Price is a big factor: African consumers want to get the most value for money they can. This ‘first phone’ category is something we have invested in heavily at Nokia, recognising that it’s a growing market.”

He adds that Nokia’s best-sellers in Africa include the Nokia 105, which retails for e15 and the firm has recently added to its portfolio with the Nokia 106 and Nokia 107 Dual SIM, and the Nokia 108 and Nokia 108 Dual SIM. All of the phones feature colour, both in the hardware and screens; expandable memory; and in the case of the Nokia 108, multimedia capabilities through the VGA camera and content-sharing with Bluetooth technology. “We’ve completely re-imagined what you could expect from phones priced under $30,” Turcanuo says.

Despite such a modest smartphone user base, mobile usage habits in Africa are on the whole relatively mature. Having been excluded from the PC revolution by price and lack of fixed connectivity, many African nations are not only mobile first, but essentially mobile only markets. From Somalia to Kenya, mobile phone users are able to pay for petrol, bills and groceries using their mobile handsets, and m-learning is emerging as an affordable option for education in many regions—a scenario that leading operators and handset manufacturers are striving to now recreate in mature markets.

So while the growth of the first phone category has been an important trend, attention is now turning to more advanced feature phones and smartphones which are reaching new levels of affordability, and driving huge adoption.

In August 2012, the region’s top selling handsets included the Nokia XPressMusic 5130 and Samsung’s E250 handset. Both are 2G devices, which support GPRS and EDGE data connectivity. Such feature phones have formed the bulk of handset sales since 2011; Nokia’s Asha range is one example of this “smarterphone” range, as the firm calls it. These handsets come in QWERTY or touchscreen form factors and the majority are restricted to GPRS and EDGE, although the 300 series also supports 3G network connectivity.

“Nokia Asha was developed for young, aspirational consumers in fast-growth markets,” explains Turcanu. “They responded very well to the Asha family’s design, ease of use, and apps. Regionally, the Nokia Asha 305 was the top-selling smartphone in IMEA for seven straight months, and the Asha 200 was the top-selling QWERTY device of all time.”

However, rival handset manufacturers have become aware of the opportunities offered by the African market and have eroded Nokia’s market dominance. Canadian manufacturer BlackBerry, whose travails in the rest of the world have been even worse than Nokia’s, has been able to drive popularity in key African markets, such as South Africa and Nigeria. Vodafone’s African subsidiary Vodacom said recently that it had 3.1 million BlackBerry devices on its network in South Africa in May 2013, compared with one million Android, 600,000 iOS devices and 165,000 Windows devices. As a result, BlackBerry has been paying more and more attention to Africa lately.

“In September 2012 BlackBerry opened its first Nigerian office and branded store. BlackBerry has also set up three Apps Lab app-development centres in South Africa,” explains Matthew Reed, principal analyst, Middle East and Africa, in a research note published by Informa Telecoms & Media.

Korea’s Samsung, which dominates the global smartphone market, is also addressing the opportunity in Africa. The firm has a number of initiatives for the African market that extend beyond devices, such as a partnership with Universal Music to develop a Pan-African mobile-music-streaming service.

“Steady sales of Samsung’s low- and mid-tier devices to emerging markets appear to have validated the vendor’s decision to increase the proportion of those devices in its portfolio,” says Reed. “Smaller players are also targeting Africa. Mauritius-based handset brand Mi-Fone, which was set up in 2008 by entrepreneur Alpesh Patel, has established itself as a provider of low-cost, data-oriented devices in Africa, aimed at the continent’s aspirational, fashion-conscious youth market. The devices are manufactured in China, though Mi-Fone reportedly plans to build a factory in Nigeria.”

Chinese vendors, such as ZTE and Huawei, are also gaining traction in the region, due in part to the close relationships they have with operators as infrastructure suppliers and their focus on low-cost handsets.

Huawei has teamed up with Microsoft to bring the 4Afrika smartphone to market, which is based on Huawei’s

Ascend W1 model. The device was unveiled in February 2013 and according to Microsoft, is targeted toward university students, developers and first-time smartphone users. The project aims to ensure they have affordable access to technology to enable them to “connect, collaborate, and access markets and opportunities online”.

The pricing of handsets is clearly vital to uptake in Africa and, according to Lv Qianhao, global marketing director of Chinese manufacturer ZTE’s handset division, the price point for an entry level smartphones is gradually descending.

The pricing of handsets is clearly vital to uptake in Africa and, according to Lv Qianhao, global marketing director of Chinese manufacturer ZTE’s handset division, the price point for an entry level smartphones is gradually descending.

“Last year, the price of entry level smartphones was about $120. This year the price of a 3G smartphone is under $100 but, despite the drop in price, the hardware is much more powerful compared to the old model. So we think that when the price of the entry level device reaches $90, or perhaps $60, then the smartphone will replace the feature phone in Africa.” He adds that the coming three years are likely to change the dynamics of the region significantly.

A key reason for the drop in smartphone prices is the decline in the cost of the components used to create them. Silicon vendor Qualcomm says that it is actively trying to drive down the cost and price of its components for emerging markets and is working with local handset makers to help them bring high quality and low cost devices to market.

“Qualcomm’s Reference Design Project has been implemented to help address primarily the critical needs of emerging markets,” explains James Munn, VP South Africa at Qualcomm. “It involves a mixture of local investment and creating low-cost platforms for low-cost devices.”

He adds that through creating the reference design platform, Qualcomm helps OEMs lower the time spent bringing new models to market, citing African handset manufacturer Techno, which is prominent in West and East Africa, using a number of Qualcomm reference designs for its devices.

“This will move into tablets as well, because tablets as well as smartphones have been an important development in 3G adoption. By using our reference design manufacturers can significantly reduce the development costs of devices.”

Jean-Marc Polga is director for Orange’s device portfolio and oversees the original device manufacture (ODM) unit selling into EMEA. He agrees that the falling cost of components, which he argues has been driven by Chinese vendors, will create a turning point for Africa’s smartphone market penetration. He explains that Orange’s ODM portfolio for Africa is currently around 75 per cent feature phones, many priced at less than $30.

“Smartphone prices are will soon fall to around $60. For customers in this region price is a very important element—so over the next three or four years when the prices get cheaper to $50 to $60 for an entry level smartphone we’ll see an uptake in smartphone usage.”

However, price is not the only factor. As in any other region, African consumers want a stylish, well designed device that is also affordable.

“I think that the combination of form, functionality and affordability is a recipe that will win in Africa,” comments Graham Braum, GM for Africa at handset maker Lenovo, which is looking to launch smartphones in Africa in 2014. “If you look at where the analysts are expecting the number of smartphones in Africa to be by 2016, they’re talking about almost doubling the smartphone market in three years—that is huge growth and huge penetration and it shows you the appetite for technology in Africa.

“There has always been a hunger for technology in Africa—it was only ever an affordability issue, coupled with the lack of connectivity or affordable connectivity. Both of those have been addressed. Tablet and smartphones address a piece of technology that allows you to have an affordable technology which can access the internet and I think the telecommunications companies have worked really hard to get the cost of data down.”

He adds that not only are prices of smartphones, components and connectivity falling in Africa, many markets are growing economically as well, which will accelerate the rate of smartphone adoption further.

“Some seven African countries are in the top 10 fastest growing economies in the world. If you look at countries like Mozambique, Angola, Ethiopia, Zambia, Togo – all of those markets have shown exceptional growth and real stability and with that you almost get a new investment climate for these countries. This allows you to have a new emerging middle class and with that comes a very vibrant entrepreneurship culture; businessmen or ladies who want access to technology and to innovate.”

In October this year, the World Bank also raised its economic outlook for sub-Saharan Africa, forecasting that “strong domestic demand” coupled with higher production of commodities will lift the region’s growth above five per cent in 2014. It added that growth in sub-Saharan Africa was set to “strengthen” to 4.9 per cent in 2013 and would rise to 5.3 per cent in 2014—up from its 5.1 per cent projection.

Although smartphones are getting cheaper and African consumers are getting richer, there are still many hurdles facing Africa’s handset market. One issue is the prevalence of grey and black market goods. It has become commonplace in recent years in Africa for consumers deterred by the cost of devices or their lack of availability in certain markets to buy consumer electronic devices from nearby countries and import them into their home country. This activity means phones are sold through unlicensed resellers, on the grey market.

In the case of smartphones, not only are there issues regarding lack of warranties by purchasing through these means, but mobile handsets sold in different countries often use different spectrum for voice and data connectivity. This can result in consumers buying a handset that is not compatible on any operator’s network in their home market.

This is a major problem throughout Africa and around 30 per cent of handsets in use in Africa are bought via the grey market, according to Gustavo Fuchs, business group lead for Windows Phone in MEA.

“There is a lack of local players across value chain so logistics is one of the biggest challenges in Africa and the grey markets that exists,” he explains. “These devices which often don’t work and have no warranty which decreases the speed of adoption of smartphones and the overall user experience and perception of smartphones.”

He adds that there is still a substantial volume of counterfeit, or black market, handsets causing major issues in Africa, particularly in markets such as Egypt and Nigeria. However, Fuchs notes that those firms that historically produced fake smartphones are now moving towards producing their own brand smartphones, which is a step in the right direction.

And there are other fundamental issues. Smartphones are only marginally more useful than feature phones if they do not have access to reliable networks. Data plans need to be priced in a way that attracts customers and, given that the region sidestepped the PC revolution, many African consumers still need education on the benefits that data connectivity and the internet can bring to them.

A number of African countries (see feature, p08) do not have an operator offering 3G services and as Lenovo’s Braum explains, smartphones are no good offline. But African governments in particular are aware of what data services could do to help their economies and societies and have been driving efforts in this space.

“You need to be online to really take advantage of smartphones, and that’s where I’ve seen a lot of work over the last 36 months by a lot of governments of African countries in order to get the cost of connectivity down with the telcos,” he says.

“I don’t think we can put a tick in the box yet, because there’s still work to be done, but there’s a massive amount of work that has been done in a lot of countries.”

Another opportunity for handset makers in Africa, perhaps more than anywhere else in the world, is the 50-plus age demographic, or “silver surfers”. This demographic has not had exposure to technology through the rise of PC penetration and, as a result, there is demand for handsets designed specifically for the older population.

“We’ve seen a huge adoption from the above 50 age group; they are really embracing technology,” says Lenovo’s Braum. “I think the touch interface is natural and makes sense [to this demographic] and I think technology has just become that much easier to use. We’ve seen a huge emerging group of customers in this age group.”

ZTE’s Qianhao agrees and says the vendor is developing handsets specifically for this market segment in Africa, with large icons, large text and simple OS navigation.

He goes on to claim that the culmination of factors; a population with an appetite for new technologies, the construction of 3G networks, the decline in smartphone costs and a growing economy, could make Africa ZTE’s most important region before long.

“Currently our share of global mobile revenue from Africa is around five per cent,” he says. “However, we think that after three years, the revenue from Africa for ZTE [devices] will increase three-fold. It’s going to generate a lot of demand and ZTE believes that Africa could become the most important market for ZTE.”

It is clear why handset manufacturers and other stakeholders in Africa’s mobile sector are optimistic about the future. However, despite the expected rise of smartphones over the next three years, the industry needs to keep its feet on the ground and not forget about serving the mass market and non-mobile users. Feature phones are still expected to dominate in Africa for the foreseeable future, and as Microsoft’s Fuchs says:”The ten per cent is important, but more important is the 90 per cent.”

Read more about:

DiscussionAbout the Author

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

_1.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)