The Clone Wars

The handset market is more competitive than ever, and success is increasingly being defined by performance at the top end. 2012 will be the year of the Windows Phone push but can Nokia and Microsoft really compete with established leaders like Apple, Android and Samsung?

February 13, 2012

The final quarter of 2011 was an eventful one in the handset sector. Nokia marked its return to the smartphone market and its first Windows Phone product with a great deal of fanfare, while Apple announced in quick succession the availability of the iPhone 4S and the death of its inspirational leader Steve Jobs. Samsung released the first handset to run version 4.0 of the Android OS and Sony Ericsson announced that its tenth birthday would be its last, as Ericsson finally exited the joint venture and Sony absorbed what remained.

Meanwhile Chinese vendor Huawei set out its stall, pledging an assault on the smartphone market to match the one it has mounted with such success on the infrastructure sector. Alcatel, a handset brand far less prominent in 2011 than it was in its heyday, surfaced in partnership with Orange and Facebook, as the social networking firm revealed more of the cards it plans to play in the device space. For Blackberry vendor RIM, the situation simply went from bad to worse; leading to the resignation of co-CEOs Jim Balsillie and Mike Lazaridis in January.

And these were just the headlines. Behind the biggest stories, the device sector continued to pulsate with activity in 2011, as its constituent parts battled for their place in the value chain, the hearts of the consumer and for supremacy over one another.

For all the change, one constant remains: the mobile operator is still the primary route to market for handset vendors. And competition for a place in operators’ portfolios looks set to intensify. In November Matthew Key, head of the Digital unit at the newly restructured Telefónica, revealed that the firm is planning to slash the number of handsets in its global range by more than half.

With a portfolio of around 240 handsets, there is clearly a lot of fat to cut at Telefónica. But while the firm’s device range is at the larger end of the scale, relative to subscriber base, Key’s announcement reflected a trend visible in the wider industry.

Simon Lee-Smith, general manager UK and group devices at Telefónica, says that the surplus in the portfolio can be explained by a handset strategy that has historically been local in focus, with individual territories responsible for procuring handsets deemed especially suitable for their markets This is now changing to a more “aligned” approach, hence the cut in numbers, which will happen mostly at the low end.

At Vodafone, where the device portfolio is currently at the kind of size that Telefónica is targeting, the drive is to reduce the range still further, says Peter Becker-Pennrich, global director of terminals marketing. Becker-Pennrich says that Vodafone plans to “go down in size quite a bit” in 2012. And a similar strategy seems likely at Orange and Deutsche Telekom, which have announced plans to align procurement of handsets. Orange currently ranges around 100 handset models per quarter, according to Patrick Remy, the firm’s senior vice president for devices.

Remy says portfolio management needs to take into account the fact that too much choice can confuse consumers, but Dan Adams, a partner at Accenture who focuses on device strategy, points out that there is also a key financial driver.

“The research that we’ve carried out into the prices that manufacturers charge operators shows that, until you hit between 500,000 – 750,000 units, you don’t reach a manufacturer’s best price,” he says. “So operators have to set their portfolio so that a good chunk of it gets over that number per device. If they don’t, they’ll be paying more than the competition and, while they might have a better range of handsets that’s more adjusted to the local market, consumers are not going to pay more for a handset they can get cheaper elsewhere.”

Vodafone spends $8bn on handsets annually, according to Becker-Pennrich, including affiliates and partner markets, which translates into 60 – 70 million units a year. Telefónica’s Simon Lee-Smith says annual device spend is around $6bn, which buys some 50 million devices. Patrick Remy doesn’t want to say how much he spends at Orange, but indicates that he buys in the region of 30 million units annually. With those kind of shipment numbers, it’s easy to see why—according to Accenture’s calculations—the range of devices on offer needs to be carefully restricted.

The worry for vendors is that a cut in the number of devices on offer might translate into a cut in the number of suppliers. At Vodafone just eight suppliers deliver 98 per cent of the volume, and Becker-Pennrich says that he “would expect the number of suppliers to become less.” Telefónica has around a dozen “key vendors” of which half are deemed “strategic suppliers” that are able to deliver breadth and depth. A reduction in the number of suppliers is not a goal, says Lee-Smith, but the firm expects “natural consolidation”.

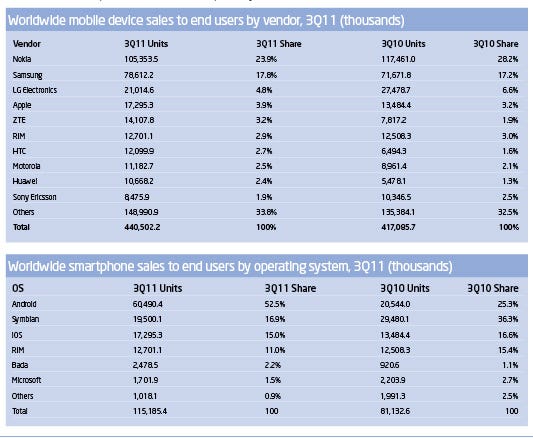

smartphone worldwide figures

None of this paints a rosy picture for handset vendors and, mindful of the importance of the carriers in getting to market, they don’t want to ruffle any feathers. Apple aside, which in terms of operator relationships is in a shot-calling class of its own, the vendors seem universally keen to portray themselves as the operators’ friends and supporters. Sony Ericsson’s global head of sales, Kristian Tear, is a deferential case in point:

“We have no ambition to replace operators,” he says. “They have acquired expensive licences, built out infrastructure and—to a large extent—they facilitate the development of mobile phones and mobile broadband. So we try to work together with them.”

As if to reinforce the message, Simon Lee-Smith offers a thinly veiled warning to handset manufacturers when he says that the vendors which don’t recognise the “end to end value chain of devices”—for which read the interests of the operators in that value chain— “rarely do well.” There are some vendors, he says, without naming names, whose interest wanes once the operator has bought their product. How to sell this product onto the consumer is the operators’ problem, as far as these players are concerned—a position which doesn’t win much favour with Lee-Smith.

“That’s a very myopic view,” he says, “and we won’t support those vendors.”

In truth, though, the handset vendors don’t need threats to motivate them. For most of them a new reality is dawning in which, despite their protestations to the contrary, differentiation is becoming increasingly difficult. The launch in October of Huawei’s first own-branded Android smartphone, the Vision, offers the perfect illustration: It simply wasn’t clear what a consumer would see in the Vision that set it apart from the alternatives from Samsung, Sony Ericsson, HTC and the rest of the Android collective.

Peter Becker-Pennrich argues that, while there are actually differences between the handsets from the various players, the customer perception is that differentiation between them is minimal. Consumers typically gravitate towards the large brands, he says, making it very hard for the chasing pack to pitch any kind of USP.

“What happens at the beginning of the innovation cycle, typically, is that whoever owns that innovation is able to capitalise on it and build a brand value,” he says. “Later on, as the innovation cycle flattens out and more people can do it—and price goes through

the floor—it’s very difficult for the players that were not part of the first wave of innovation to explain to customers why they should pay a premium for their brands.”

Given that Apple alone can claim to have truly owned the current innovation cycle from the outset, all of the other vendors fall into the second wave and are battling one another for stability in the market. Those that are successful—Samsung chief among them—are forced to navigate the obstacles placed in their path by Apple’s aggressive legal strategy.

The problem is compounded by what some handset sector executives have identified as the beginnings of a shift in loyalty away from handset brand in the high end towards the OS. “The growth of Android has demonstrated that customers value the operating system,” says Telefónica’s Simon Lee-Smith. “Increasingly people are coming in and asking for an Android device, rather than a Samsung or Sony Ericsson.”

As handset brands have historically held greater sway than operator brands, vendors and operators are bound together by the shared threat from the platform players like Apple, Google and—if it is successful with its revamped Windows Phone offering—Microsoft.

For Microsoft, being perpetually late to the party could finally be construed as a positive, at least in terms of the reception it’s now getting from operators. None of the carriers feel safe with a smartphone platform duopoly that Accenture’s Dan Adams categorises as “Apple at the top and Android at the bottom.”

Peter Becker-Pennrich says that this duopoly “feels uncomfortable”. Like all operators, he bends a knee to Apple, saying: “It’s no wonder they are the most valuable tech company in the world right now, because they have the best content, delivered through the best processes.” And his take on Android is also positive. While iOS “makes it difficult for us to push our services and differentiation agenda,” he says, Android scores highly for operators on issues like commercial flexibility and the ability to pre-embed and deeply root carrier software into the OS.

“The only problem,” he says, “is that if Google had a bad day and changed all of its policies, there would be relatively little that the industry could do about it. That’s where a lot of the discomfort is coming from, and we need more competition in that space.”

Once upon a time carriers would have looked towards Blackberry vendor Research in Motion for the third platform, but those days are long, and perhaps irretrievably, gone. When Orange’s Patrick Remy says, “having only two ecosystems would be something that we’d be concerned about—having a third is important to us and our customers,” he offers a damning assessment of RIM by not even considering it as a prospect.

Microsoft’s bid to exploit this need for a third ecosystem, and to drive quality technical and strategic execution, will surely be one of the great device sector narratives of the next twelve months. And it is not only Microsoft’s fortunes that this narrative will chart; Nokia, too, is fully exposed to whatever difficulty or reward lies in store for Windows Phone.

The launch of Nokia’s Lumia 800 was arguably the biggest product story to emerge from the handset sector in 2011, and with good reason. Once arch-rivals in the handset space, Nokia and Microsoft now depend on one another for success in what is, for both of them, the latest (and possibly last) of several costly and involved rolls of the smartphone dice. Both of them talk of the importance of growing the WP ecosystem, with the participation of other vendors key to its success. But for the time being Nokia and Windows Phone are essentially one and the same.

Microsoft’s other vendor partners, which have shifted en masse to Android during Windows’ time in the wilderness, will not rush back to Redmond until they’ve seen how Nokia performs—not least because the exact nature of the relationship between Microsoft and Nokia, and in particular the level of favouritism the Finnish vendor will be shown as part of it, is not being communicated. So when Nokia’s UK and Ireland MD Conor Pearce says “we’re trying to build a third ecosystem, to bring balance to the market” and “we’re proud to be doing the first real Windows Phone,” he is positioning Nokia, as well as Windows, as the answer to carriers’ concerns over the platform duopoly.

And few people seem willing to write the partnership off. “The market is open for Microsoft and Nokia to have a really good play here,” says Accenture’s Dan Adams. “Microsoft have never really cracked the handset market but never bet against them in a consumer play. Just ask Sony Playstation if the Microsoft brand is cool enough to sell to consumers. And one thing that can be guaranteed is that Microsoft will be able to create a good development community.”

The marketing push that Nokia is putting behind the Lumia 800 is immense and, if the phone falls short of expectation, it won’t be for lack of consumer awareness. Taking its lead from Apple, the Finnish vendor is looking to position its new flagship firmly at the premium end of the market and this aspiration may be one stumbling block to success, at least if the views of Telefónica’s Simon Lee-Smith are any measure of the situation.

“Nokia are coming back at high end levels, but generally Nokia devices are expensive—and if they want to sell in volume they need to bring out devices that are cost competitive,” he says. “Manufacturers seem to think that a €400-plus price is the norm. Well, it isn’t; customers and operators won’t pay that level of cost for a device which doesn’t differentiate sufficiently.”

Nonetheless, Lee-Smith—like his opposite numbers at Vodafone and Orange—stresses enthusiasm for the Lumia 800 as well as the wider Windows platform play. And, while we’ve seen how important it is for vendors to support carriers in the handset space, the relaunch of Windows Phone illustrates how that support can travel in the opposite direction. At Nokia World 2011, where CEO Stephen Elop unveiled the Lumia 800, he said that the operators carrying the new handset would be spending three times as much on marketing it than had been spent on any other Nokia handset.

In the UK, Telefónica’s O2 has a phalanx of in-store sales specialists called Gurus, schooled to a specialist degree in the workings and strengths of various handsets within the carrier’s range. The closer the vendors work with the Gurus, says Simon Lee-Smith, the better the Gurus will be at selling their handsets. “The Guru programme has been very successful,” he says, “and it has increased sales for all of the vendors that have been involved in the programme.”

So Nokia, like the rest of the vendors in the high end market apart from Apple, will now adopt a pro-carrier stance. This position is neatly summed up by Sony Ericsson’s Kristian Tear in a comment aimed squarely at Apple (and one that might perhaps be aimed at Google, too, were it not for Sony Ericsson’s commitment to Android): “We want to support the operators, rather than try to steal their customers and consumers away from them, and we’ll continue to do that.”

A dynamic that sees the market leader challenging for customer ownership and the chasing pack pledging allegiance to the operator community is nothing new, of course. While New Nokia would never do such a thing today, it was not that long ago that it launched Club Nokia, which can be viewed in hindsight as an overly premature or poorly executed (or both) attempt at the strategy that Apple made its own. And when Nokia was making its bid for supremacy, its peers made similar noises about the importance of the carrier. Club Nokia did not sit at all well with the operators, and its failure gave credibility to the unsupportive stance they adopted. There was no such attempt to stand firm in the face of Apple, however, and just as the chasing pack of handset vendors make all the right noises about the importance of the operators, so the operators themselves cannot be seen to bellyache about the level of control Apple exerts over them.

And yet it’s an open secret that the carrier community harbours a level of resentment towards Apple. Of course very few people want to put their head above the parapet and say so; for an operator spokesperson to voice any sentiment along these lines would probably be a firing offence. But even third parties and partners get extremely jittery on the topic.

One man who doesn’t mind calling the situation as he sees it is industry consultant Bengt Nordström, a former CTO at Hong Kong carrier SmarTone and alumnus of Ericsson and Comviq, among others. “We hear from the operators about how Apple treats them and they’ve never seen anything like it before in the industry,” Nordström says.

“When [Apple] began to dictate the situation, questioning whether operators were good enough to sell their product, it conflicted with the views that operators have of themselves.”

The problem is compounded by performance issues with iPhone products that operators, in many cases, must shoulder, he says. “Many of these problems are caused by Apple’s technical solutions, such as their poor radio antennae,” he says. “But when they try to bring these things to Apple’s attention, they get ignored.”

For Apple, undisputed over the past four years as the leading innovator in the smartphone space, 2011 will go down as one year in which the key milestone was not product related. The death of Steve Jobs overshadowed the launch of the iPhone 4S and forced the industry to confront what it had long been debating hypothetically: Can Apple continue to dominate without its leader—a complex character who will be remembered as much for his ruthlessness and dictatorial management style as for the clarity and genius of his vision.

For Tim Cook, who replaced Jobs as CEO when Jobs’ illness made it impossible for him to continue to lead, the pressure is well and truly on. While his debut performance unveiling a new product was made under the pall of Jobs’ imminent demise, the iPhone 4OS itself met with nothing like the positivity that greeted its forebears. The world was waiting for iPhone 5, and what it got was Siri; a voice control function that sits alongside Facetime as another attempt from Apple to breathe life into a concept that the mobile industry has long used to define the future. While Vodafone’s Peter Becker-Pennrich pays tribute to Apple’s successes, there is a caveat attached: “The question is whether or not the will have the best product going forward,” he says. “The iPhone 4s was a disappointment to many people and—if you forget about brand value for a moment and compare it to a Galaxy Nexus of SII, or the HTC sensation—you’ll find many reasons why the iPhone wouldn’t be rated as high as the others.”

Whether or not Apple can sustain its status as the definitive innovator in the space is probably the biggest question in the smartphone market for the near term. Certainly the technological gap between it and its competitors seems to be shrinking. Simon Lee-Smith says that Apple still out-executes its competitors and retains a design edge. But he adds that, “the others have brought themselves much closer to iPhone and Apple in general. The gap is closing—and closing rapidly.”

Of course the question of whether Apple retains its leadership leads to another, more open debate: If Apple is to be ousted, who or what will succeed it? Even the people most intimately involved in the handset sector concede that they’d be far wealthier by now if they had the answer to this question. But there are a few ideas.

There is a consensus that, any player that is able to make a true success of a domestic, multi-device connectivity play—somehow harnessing the benefits and experiences available through the television, the PC, the smartphone, tablet and other devices (games units, for example) could find themselves in a very strong position. “Whoever gets that right first will be able to command a premium on their products in the phone space,” says Becker-Pennrich.

Such a trend would play well for the likes of Samsung; strong in TVs and handsets, and working hard to become so in the tablet space. The new Sony device business, when the Ericsson half of the brand has been phased out, will be all about adding “Sonyness” to the products, says Kristian Tear. “We believe in the convergence of screens and this is putting us in an excellent position for the next five to ten years,” he says.

Simon Lee-Smith is thinking along similar lines, addressing the question of whether whichever company usurps Apple will have to exert a similar level of control from one end of the device play to the other. “I think Apple will be challenged by a company that has end-to-end control, but not necessarily of hardware and software,” he says. “Someone will bring out an integrated solution which offers software, services and connectivity as a whole, and it won’t be about the looks of the device. There will be another competitive landscape, and this is where other companies will leapfrog Apple.”

In the immediate term, as the smartphone innovation cycle winds down, tablets will lead the next one and, here, Apple looks to have already established another leadership position. Given the similarities in the DNA of smartphones and tablets, however, the chasing pack are already showing themselves to be far quicker off the mark, and the tortuous legal battle between Apple and Samsung, is likely only the tip of the iceberg.

As the carriers, vendors and platform providers tussle for position, they are in chorus on the view that the consumer holds the final decision-making powers. In the end it will be down to the consumer to judge whether or not the Lumia 800 is worth a certain amount, or whether Android has evolved to the point where it is no longer perceived to be a poor cousin to iOS. It will be the consumer whose loyalties will reflect the strengths and weaknesses of all the players in the value chain and the consumer who decides what innovation is the winning innovation. And it should not be forgotten that there is a distinct possibility that the next great innovation leader in the device space is not a name even known to that consumer as 2012 unfolds.

P.Becker-Pennrich

Peter Becker-Pennrich

A buyer’s perspective

As the director of marketing for Vodafone’s global device unit, Peter Becker-Pennrich is closely involved in the procurement of up to 70 million mobile devices each year. Like all operators in mature markets, Vodafone has an interest in seeing a third smartphone ecosystem thrive in a market dominated by Apple and Google. Here Becker-Pennrich gives his frank assessment of the prospects for Nokia and Microsoft as they spearhead the Windows Phone challenge, and his thoughts on Research in Motion, which at one point would have been viewed as the natural provider of a third way.

On Windows Phone…

WP is not there yet. They are making genuine efforts for WP8 but in WP7 there is still a lot to be wished for, especially when it comes to offering all those things that we need on the enterprise side, and the overall flexibility of the OS.

On Nokia…

Success isn’t guaranteed, but it’s not all doom and gloom, as you sometimes see in the analyst opinion pieces. They still have one of the strongest and largest supply chains in the world and their economies of scale are significant. And they still have a significant presence in all the markets that they operate in. They know how to work the channels and they have the sales structure in place.

They still have brand value, and a lot of brand recognition, which is a dormant asset. If they manage to underpin that with more attractive products then I can see how a lot of these things can be leveraged again. Will they succeed for sure? I don’t know, but they have a fighting chance and therefore I’m tentatively optimistic.

On Microsoft…

I continue to be confused by Microsoft’s stance in the smartphone market. On the one hand they want to provide a fairly rigid, streamlined experience because they say they don’t want to confuse the consumer and they want to offer a recognisable experience. But this is of no value to anyone in the ecosystem other than Microsoft.

They want to be restrictive with their experience and at the same time they want to appeal to as many OEMs as possible—and you just can’t square that. Why would an OEM be interested in taking the platform if they can’t differentiate on top of it?

On the Microsoft-Nokia partnership…

My long term expectation is that, at some point, Nokia and Microsoft will become one, but not necessarily from a financial or corporate entity perspective.

On Research in Motion…

RIM reminds me right now of Nokia around the time when they were selling the N97 and a bit later. If you have strong leaders who take credit for leading the company to its present position, they really struggle to see that they shouldn’t be the ones who take it forward. I’m not sure whether RIM entirely understands the magnitude of the problem they have; I don’t think it has completely sunk in.

What are their options? Licensing another OS doesn’t really make any sense because, what makes your Blackberry really valuable is not the UE, or the integration, it’s the unbeaten ability to have push email with very decent battery life that is stable and robust. They took a lot of flack for the outage recently, but they ran so many accounts for so many years with no problems. That’s their strength. And the special sauce of this thing is just about where the silicon hits the software. So it’s not going to be easy for them to put some standard software on top of their hardware and then somehow make best use of everything they’ve developed.

It will be a massive effort, but I think they will go for an open OS which they don’t control, which is why they made the QNIX purchase.

Read more about:

DiscussionAbout the Author

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

_1.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)