A look at China’s tech crackdown and its wider implicationsA look at China’s tech crackdown and its wider implications

Didi’s delisting from New York offers a case study of China’s more assertive approach towards the country’s big tech and the ramifications that go far beyond its borders.

December 6, 2021

Didi’s delisting from New York offers a case study of China’s more assertive approach towards the country’s big tech and the ramifications that go far beyond its borders.

Only months after its fanfare-less IPO on NYSE, Didi Chuxing, China’s answer to Uber, announced on Friday that it would start the process to delist from the New York bourse and move to go public in Hong Kong instead. Didi has been under an inter-departmental investigation by the Chinese authorities, which were clearly irked by the company’s decision to press ahead with the public listing at the end of June, despite being warned not to do so. Although the results of the investigations have not been published nor have punishments been handed down, delisting looks to be one of the requirements.

This is a high-profile but by no means isolated case. indeed, it is just the latest episode of China’s recent crackdown on the tech sector, which started almost exactly a year ago. It’s worth taking a step back and treating Didi as a big case but also one of many. This article aims to examine the main threads of recent state intervention in the tech sector, the rationale that has driven such heavy-handed measures, the intended and unintended results, and what all these mean to the outside world.

What has happened?

While the Chinese authorities have never been a genuine believers in leaving the market alone, and would not hesitate to replace the invisible hand with a visible one, the scale and intensity of state crackdown on the country’s big tech companies over the past year is unprecedented in recent history. The following is a broad timeline of the major events that have bearings on the topics of this article.

Since the end of last year hardly a week would go by without the world hearing of the Chinese government bringing yet another high-flying tech heavyweight to its knees, so much so that the campaign, covering sectors from fintech to games, has almost become a routine. It did become quieter, however, in the run-up to the beginning of July, when the ruling Communist Party marked the 100th anniversary of its founding, before it resumed in the summer. The campaign seemed to have entered a hiatus when the Communist Party held an important meeting to officially recognise the historic position of Xi Jinping, the party leader and the country’s president.

All these actions started with a dramatic curtain raiser. Only days before Ant Group, the financial business unit spun off from Alibaba, was schedule for its IPO in Shanghai and Hong Kong, the Chinese government pulled the plug on it. Shortly afterwards the official message came out to demand Ant Group to undergo fundamental reform before the IPO could be back on the agenda.

The impact of Act I was profound, though not always in the way the government might have had intended it to be. The last-minute order to halt may have prompted investors of Didi, China’s dominant ride-hailing business (which acquired Uber’s China operations in 2016), to make a “now or never” decision. They took the risk and went ahead with their own IPO in New York, low-profile by any standards. By that time the regulators had already started investigations into its alleged anticompetitive practices. The punishment was both immediate and severe. Within days China’s internet watchdog ordered Didi to stop registering new users and demanded all app stores to pull 25 apps run by Didi. After imposing a fine of half a million yuan (roughly equal to $77,000), the maximum amount applicable for monopolistic behaviour, the government upgraded investigations into Didi to alleged breach of data security law, which came into force days after the IPO with multiple government agencies involved.

The games industry then came in the government’s crosshairs. The government decided to suspend approvals of all new game titles and that all under-18-year-olds should not play video games for more than three hours a week, between 8pm and 9pm on Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays. This time, Tencent, the world’s biggest videogame publisher, got the memo immediately and vowed to support the government decision, without being specific on how to do it.

The moves on video games were part of an overall campaign to assert more control over the life of the country’s younger population. Earlier the Chinese government has banned for-profit after-school tutoring programmes, including all the online extra curriculum tutoring and training platforms. Some of the biggest education and tutoring businesses are pushed to the brink of bankruptcy.

Has the goal been achieved?

No matter how success is measured, the results of the recent quickfire crackdown are probably a qualified success. On one hand, the authorities have clearly taken the upper hand in subduing the tech billionaires. Jack Ma, the founder of Alibaba and Ant Group, has been silent since the Ant IPO debacle and has all but vanished from the public eye. Didi publicly announced that it would fully cooperate with the now cross-departmental investigation, and the company’s co-founder and president would step down, according to sources of Reuters. On the other hand, while Tencent may very well survive the latest round of crackdown on the gaming industry, if historical precedent is anything to go by, many small games companies can expect to shut the door for good, as thousands did in 2017 when the government suspended approval of new game titles.

The follow-up, knock-on, and spill-over effect of the crackdown is more pronounced. More than half a year after Ant’s IPO was suspended the company’s fate is gradually made clearer: it will be split into independent businesses handling payment, loan businesses, and credit scoring. The state will take a sizeable stake of the credit scoring arm through a joint venture. Didi’s president, according to Reuters, expected the state to take control of the company eventually.

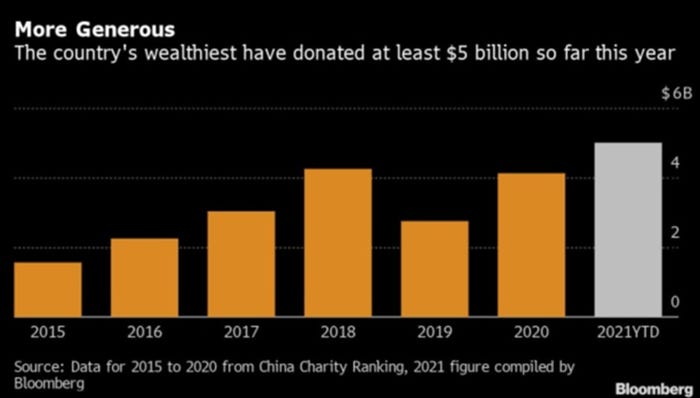

Other high flying tech companies not in immediate danger of being nationalised also read the message quickly and have taken actions to win goodwill from the state. The most noticeably actions taken are generous donations in response to the government’s call for charitable giving as a “third means of distribution” (after wage and tax payment). According to data compiled by Bloomberg, donations by seven of China’s billionaires by late August had already reached $5 billion, 20% higher than the national total of 2020. Most of the donations are earmarked for causes the government wishes to nurture, especially education and technology innovation. Billions of future giving has also been pledged. Tencent set aside $15 billion of its future profit for corporate social responsibility programmes.

An old Chinese saying goes “kill the chicken to scare the monkey”. If that’s the effect Mr Xi meant to drive with the recent crackdown on tech companies, he has certainly overachieved. Not only do the Chinese companies not directly punished get the memo, but global heavyweights have also got the message. In recent weeks, LinkedIn and Yahoo both announced that they were closing operations in China, citing “a significantly more challenging operating environment”. Soon after, the Chinese version of Fortnite, one of the more popular game titles developed by Epic Games and operated by Tencent in China, shut down in mainland China.

On the regulator front, the SEC has halted IPOs by China-based companies unless they fully disclose their legal structure and, more importantly, the risk of interfering in their businesses by the Chinese government.

However, individual and corporate donations on top of the penalties tech companies have been fined or expected to be fined, are nothing compared with the value of the losses suffered by these companies in the financial market or the contraction of their perceived value. According to calculation done by The South China Morning Post, by late August, the regulatory crackdown had ”wiped out around US$1.5 trillion of value from (China’s) tech stocks”. It looks as if the Chinese government has worked so hard to get the ”third distribution” working that it has damaged those companies’ capability to carry out the first and second, which begs the questions: why?

But why?

Like with any other regime where a single supreme leader pulls all the strings, it is hard for observers to completely decipher President Xi’s rationale for crushing many of the country’s world beaters. To read from information made available through different channels, however, there seem to be multiple layers of reasons that could help understand China’s crackdown on its leading tech companies.

Ideology. This is both on individual and on collective levels. As an individual, Mr Xi is both a staunch Leninist and a strong believer in his own destiny. He seems to genuinely loathe the vast and widening gap between the rich and the poor created by the almost unbridled market economy unleashed four decades ago, and to believe those that have become rich should share the spoils with those left behind. The means to do so, however, looks to be through his direct command only. That famous quote ”I am sure I can save this country, and no one else can” comes to mind (Pitt the Elder, 1756). Such convictions may well have been a key driver behind his move to do away with the presidential term limits, rubber stamped by the legislature (”The People’s Congress”) in 2018, and his historic inevitability has just been institutionalised at the Communist Party’s plenum in October.

As an organisation, the ruling Communist party, the biggest political party in the world with close to 100 million card-holding members, is an aggregate of competing factions. There is the far-left group that have lamented the loss of the years of egalitarianism (at least an egalitarian venere) under Mao. There is the right wing of the party that complains, albeit silently, that China is more and more being put under an authoritarian regime already too similar to the Mao era. Mr Xi looks to be more aligned with the former group and doesn’t hesitate to show the latter who runs the show. Bringing the high flying billionaires, many of them Party members (for example Jack Ma), into line is one of the most visible and most mass-pleasing ways to demonstrate his, and the Party’s, authority.

Industrial policy. Despite that China has been the single largest beneficiary of globalisation and the globalised market economy, China’s leadership has never fully embraced the idea of open market and giving everyone a level playing field. It has always kept the so-called “strategic sectors” firmly under state control and made them off limits to foreign competition. One of such sectors is what is called “basic telecoms”, that is the telco market where operators own their networks (as opposed to “value-added communications” which mostly refers to the so-called OTT services, which is open to foreign businesses. Censorship on what can be offered is another matter.) The restrictions have been kept in place despite the explicit concessions China made when joining the World Trade Organisation that these sectors would be opened after a ten-year protection period.

It is therefore not inconceivable that the government should attempt to rein in Alibaba and unplug Ant Group’s planned IPO, when it realised that the position of state-owned banks and other financial institutions is being threatened. It was disclosed in the Ant’s Prospectus that it was already handling one-tenth of all the country’s non-mortgage consumer loans.

Data security. China isn’t known for its strict protection of privacy and personal data. Paradoxically it has been argued that the easy access to abundant user data, from facial recognition to online shopping records, has helped China’s tech companies make faster progress in AI and ML than their competitors in North America and Europe.

Meanwhile, China is also one of the first countries to insist on “data sovereignty” and, thanks to its market size and the power of its government, most if not all companies have complied with the demand to store user data in China. However, China’s definition of sensitive data is broad and not as clearly defined as in similar legislations in other markets like the EU’s GDPR, probably deliberately made so, which gives the regulators and authorities much more leeway to press charges against companies they deem not a full-on ally.

One of the major faults the authorities have found with Didi’s IPO was exposing user data and map data, which is deemed a national secret in China, to the company’s foreign shareholders, including Softbank, Uber, and Apple. The charge may be stretched, but the concern over losing tight grip on data looks to be genuine.

The new data security law that came into force in July requires companies with more than one million users should get clearance from cybersecurity authorities if they seek public listings overseas, including in Hong Kong. Some have speculated that Didi’s haste to go public at the end of June was a last-minute attempt to dodge the upcoming law.

Another company that has found its wings bound, if not clipped, by the recent tightening of data rules is Tesla. Despite pledging to meet the data sovereignty requirements by building more data centres in China and keep data generated by its electric cars sold in China inside China, Tesla has seen more restrictions put on what data electric cars can collect. “The new requirements likely will make it harder for Tesla to develop and deploy autonomous vehicles in China, because these rely on an array of sensors that collect vast amounts of data,” analysts and industry executives have told WSJ.

Transactional. The most direct and likely the most superficial rationale behind the recent crackdown on high-flying tech companies is to levy a retrospective corporate tax through fines. The amounts of fines vary from case to case. The most often pressed charge is anti-competition. The single highest penalty so far was handed out to Alibaba in April at a value of $2.8 billion for its monopolistic behaviour. This was roughly equal to 4% of the company’s annual revenue from China the previous year. The dominant food delivery platform Meituan found itself on the receiving end in October of another hefty fine on the same charges. The amount of $534 million was equivalent to 3% of the company’s annual income.

Sometimes groups of companies may be punished together. In March this year, 12 companies were fined the maximum amount under the anti-monopoly law (CNY 0.5 million, roughly $77,000) for failing to disclose M&A deals in advance. In July, five companies were punished with the same size of fines for investment deals that amounted to market concentration. The usual suspects of Alibaba, Tencent, Didi, and Meituan were present in both batches of punishment recipients. The amount of fine is miniscule for these billion-dollar tech giants, but the message is clear: no company is too big to evade punishment.

It cannot be denied that campaings like these have produced some benefits for consumers and small businesses. After the government started punishing internet giants for imposing ”exclusivity” clauses on retailers using that platforms, Tencent and Alibaba have started opening up their platforms stopped blocking links to their competitors.

But in addition to these tangible, mass pleasing results, what can international businesses and investors take away from the campaigns?

What does it mean to the rest of us?

The heavy-handed treatment of the big tech companies and the intensified data security legislation in China have multiple implications for overseas companies that aspire to win and sustain their success in the world’s most populous market.

There is no denying that President Xi has been turning back the clock on many policies implemented by his predecessors over the past 40 years that have turned China into a world power. As Bloomberg puts it, he is forgetting the very thing that has “made China great again”. While China’s revival after Mao was thanks to everything the Communist Party was not, Mr Xi is forcefully re-exerting the control by the government and the Party (in most cases the two are the same) on every aspect of life. But this can be a double-edged sword when it comes to business success prospects. On one hand the scope for the private sector to manoeuvre and to outsmart the control is contracting. This applies to both China-based businesses and foreign investment in the country. To succeed in business needs the companies’ complete compliance with the government’s demands.

On the other hand, tightening control also largely limits home-grown Chinese companies’ global expansion ambitions, as we see in Didi’s case and SEC’s recent change in policy towards Chinese companies. This in turn suggests that businesses and investors from outside China need to recalculate the risk and benefits from their exposure to China. Softbank reported a $54 billion loss of its asset value in Q3, largely driven by the battering suffered by Didi, Alibaba and other Chinese ventures. The company announced that it is rebalancing to reduce its reliance on its Chinese portfolio.

The rebalancing has already taken place for many investors. Research by Asian Venture Capital Journal, cited in The Financial Times, shows that during Q3, for every dollar invested in China’s tech sector, $1.50 went into India. Companies may also choose to further insulate their China operations from the rest of their business, even divest if conditions require.

The most significant difference between now and 40 years ago is China’s influence has fundamentally changed. Even compared with 20 years ago, China’s capability has vastly expanded from testing how low the global price could be set to testing how far public policy can be pushed. While at the turn of the century companies like Huawei and ZTE started to set benchmarks for how much telecoms equipment vendors could sell for their products, increasingly other countries including Western countries are looking to China for policy inspirations today. China was the first to lock the country down at the beginning of Covid-19, a policy first picked up by Italy then quickly copied by many other western governments that would otherwise have not dared to venture so far with their power over their constituencies.

In the tech space, Russia’s policy to give home-grown e-commerce and fintech companies a leg up while clamping down on American tech giants is almost a carbon copy of China’s long-term industrial policy. China doesn’t lack admirers in the western democracies either, be they genuine or performative. One may dismiss the US parents who expressed their appreciation of the Chinese government’s role in limiting young people’s gaming time as ill informed. When Elon Musk hailed China’s amazing achievements on the Communist Party’s centenary, and claimed Tesla is “glad to see a number of laws and regulations that have been released to strengthen data management” which could hamstring Tesla’s ambition to develop autonomous cars in China, it is both tiring and chilling.

Tiring because it is essentially the same line rehearsed by countless western business leaders since China joined the WTO: appeasing China’s demand for technology transfer and localisation in exchange for market access. Some do it more dextrously like Mr Musk or Apple’s Tim Cook, some more awkwardly, like Ericsson’s Börje Ekholm.

Chilling it is to see how readily the world’s wealthiest man kowtowing to the Chinese authorities while ruthlessly mocking President Biden being a sock puppet of the UAW (United Auto Workers, one of America’s biggest trade unions).

What becomes almost comical was when America’s leading tech companies pledged money and moral commitment to the White House’s “voluntary” cybersecurity goals, the stance and even the language used sounded uncannily similar to those used by the Chinese billionaires when they swear loyalty to the Communist Party.

Growing apart

The saga of Didi’s IPO and its subsequent troubles is but the latest example of the continuing decoupling between China and US, and between China and the western countries in general. While companies like Microsoft and Yahoo are pulling out of China, Chinese companies are also delisting (Didi) or being delisted (China Mobile and co) from the American stock markets.

China may have used data security rules to limit what data companies, Chinese and foreign, can collect and process, similar tools are also used against Chinese outbound investments. The Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S., or CFIUS, an American governmental setup that scrutinises foreign investments, has already demanded Chinese investors divest from PatientsLikeMe, a healthcare start-up that has gathered large amount of data, and Grindr, a dating app, on data security grounds. Following the government’s designation of China as a significant counterintelligence and economic espionage threat earlier this year, the CFIUS is expected to focus more on Chinese investment in the US sectors that deal with sensitive data, critical technology, and critical infrastructure.

When it comes to market access, while China closes its strategic sectors to foreign interest, barriers are being raised to restrict Chinese investment and ownership of what the western countries see as critical, for example semiconductors.

In addition to the US, governments in Indian, Australia, as well as the European Union have all tightened rules to screen takeover proposals by overseas investment, though not explicitly to fend off Chinese attempts to take over critical business. Even in post-Brexit Britain, where attracting inward investment is not only critical to the economy but also adding a political dimension to vindicate the decision to leave the EU, investment from China is raising eyebrows too. Despite that, the toothless Johnson government gave the go-ahead to the acquisition of NWF, Britain’s largest foundry, by its Dutch shareholder Nexperia, itself owned by the Chinese company Wingtech. The fact that a deal of £63 million ($87 million) has caused such controversy is a sign that the rift between China and the western countries in general is widening.

In contrast, earlier in the year, the Italian government blocked the attempt by a Shenzhen-based investment firm to acquire a controlling stake in LPE, a semiconductor company based in Milan, because of its strategic importance. More recently the Korean government, together with CFIUS, started an investigation into the proposed acquisition of MagnaChip, a Korean semiconductor company, by a Chinese investment firm.

All these changes are suggesting that foreign companies in China and foreign investment in the Chinese market need to treat the current business and political environment there very differently from twenty or even ten years ago. They need to update their risk assessment and readjust their expectations, including the possibility that the expected global growth potential of the Chinese companies they invest in may not come true. Meanwhile, they should explore other growth alternatives, including balancing the portfolio with other emerging markets.

About the Author

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

_1.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)