Fourth Coming

2010 was a significant year for LTE as a growing number of carriers prepared to join the handful of first movers in the deployment of the next generation cellular technology.

December 6, 2010

Before 2010 rolled into being, it was being touted by some as the ‘Year of LTE’. These kinds of taglines, as we’ve seen in times past, are notorious for coming back to bite the industry on the backside. Behind the bold proclamation, one often suspects, lies the triumph of hope over the plainly obvious. So it would be wrong to look back on 2010 in its closing weeks and judge it to have been LTE’s year—but that should not detract from the fact that it has been a very significant period for the technology.

As of the beginning of October there were four countries with commercial LTE networks in operation; Sweden, Norway, Uzbekistan and USA. There are 101 operator commitments to the technology across 41 countries, according to figures from the Global Mobile Suppliers Association, which also predicts that as many as 22 LTE networks could be in service by the end of the year, rising to 50 by the end of 2012. As 2010 draws to a close there is little doubt that LTE is the technology of choice for the next phase of the mobile data boom. And that status has come at the expense of a technology that was once expected to share the 4G market with LTE—WiMAX. One of the biggest wins for LTE came in the summer with the Indian Broadband Wireless Access spectrum auction. India had been one of the last big hopes for the WiMAX community, but strategic bidding and surprise technology decisions put a sizeable dent in those hopes.

Qulacomm led the blocking play, bagging 20MHz of spectrum in four key Indian markets— Delhi, Mumbai, Kerala and Haryana— and pledged straight away to use it for the deployment of LTE networks. “Our big bet is on LTE and we wanted to make sure that there was a place for LTE in India,” said CEO Paul Jacobs after the auction closed. “We were concerned that if both of those bands had gone to WiMAX it would have helped reinvigorate that ecosystem.”

The only nationwide winner in the BWA auction, Infotel Broadband Services, was acquired shortly afterwards by Reliance Industries Limited, whose CEO Mukesh Ambani revealed his own plans to launch an LTE service in its own 20MHz of spectrum. The BWA spectrum won by Qualcomm was unpaired and will therefore be used for the deployment of TD-LTE, rather than the FDD flavour of the technology that is being deployed on a larger scale in much of the rest of the world. But TD-LTE has been one of the big LTE stories in 2010, moving from what looked like a fairly niche proposition at the beginning of the year to a strong one as the final quarter begins.

Like TD-SCDMA before it, TD-LTE was thought likely at one stage to be restricted primarily to China. But, says Thorsten Robrecht, head of LTE Radio Access Product Management at Nokia Siemens Networks, it has emerged this year as a solution with a far wider range of potential applications. “TD-LTE is really a global LTE solution, I’m very sure about this,” he says. “It has evolved so much over recent months and now I’m seeing it appearing in all sorts of countries.”

While the standard has been incubated in China, Robrecht says, the earliest deployments are more likely to come from elsewhere. He reports significant activity in Japan as well as India and Russia and even customers considering it in Australia. But TD-LTE will lag its FDD sibling and all of the deployments so far—as well as the ones that are imminent—are in paired spectrum. Still, even deployments of the FDD-based version of the technology are not expected to gather truly mass momentum until sometime around 2012, with existing mobile broadband technologies like HSPA Plus still seen as having plenty of headroom. So what is driving the early deployments? What are the benefits of being the first to market?

One organisation that is well placed to answer that question is TeliaSonera which, in December 2009, became the very first carrier to launch LTE commercial services, with metropolitan networks in Stockholm and Oslo. It has since switched on LTE services in more cities in the two countries as part of its bid to hit 25 more metropolitan areas in Sweden, and the three next largest cities in Norway by the end of 2010.

Håkan Dahlström, the firm’s president of mobility services, was insistent that being the first to launch the new technology gave the firm a genuine competitive advantage over its peers. “LTE gives us the opportunity to give our customers high quality access and to really prove to our customers that going with TeliaSonera is a future-proven choice,” he told MCI earlier this year.

NSN’s Thorsten Robrecht is similarly convinced of the first mover advantage in the LTE sector. “We really see that there’s a race going on—a competition where the earliest carriers will win,” he says. “Just look at the rural coverage issues in Central Europe. The challenge for mobile operators is to beat the fixed carriers that are just offering voice. The first to come will be the one that gets the market, and operators are being very aggressive about this at the moment,” he says.

But for other operators, LTE is more of a strategic necessity than a chance to demonstrate technical prowess and leadership. Carriers that have followed the CDMA technology route, particularly in the US, do not have the luxury of HSPA, and the time and space it gives carriers to play with. So US CDMA players are more urgent in their approach to 4G technology.

stockholm-sweden

Stockholm, Sweden

It was a toss-up between market leader Verizon wireless and fifth placed Metro PCS—which is a regional rather than national carrier—as to which operator would be the first to launch LTE on US soil. In the end, it was the smaller player, driven by the fact that it had never taken the 3G step on the CDMA evolutionary path. Metro launched LTE in Las Vegas and then Dallas/Fort Worth at the very end of September. It was a double landmark, as Metro’s deployment saw the first appearance of commercial LTE handsets anywhere in the world, with previous deployments restricted to dongles for laptop users.

But analysts had words of caution for the pioneer carrier: “Metro PCS has put its name in the mobile history books by becoming the first mobile operator in the world to launch an LTE handset. But it’s a risky move because handsets using new mobile technologies take years to develop and this one is very early,” said Mike Roberts, principal analyst at Informa Telecoms & Media. “This could lead to problems such as poor battery life and dropped calls or data sessions, which happened with early WCDMA and WiMAX handsets.”

Samsung was the handset vendor responsible for the first LTE phone, The ‘Craft’ and Metro has said that it plans to have ten LTE handsets in the market by the end of 2011. The carrier hasn’t named any other suppliers, although it has signalled that Chinese vendors— presumably Huawei and ZTE among them—are pushing hard to get into the business.

Verizon is currently planning to launch in somewhere between 25 and 30 US cities in November this year, covering 100 million potential users. And like other early launchers, and perhaps with the kind of concerns set out above by Mike Roberts in mind, the US market leader has opted to launch with dongles and datacards, planning a handset-based offering some time in the first half of 2011.

The US was the site of another key LTE development during 2010, with the announcement that a new operator, Lightsquared, is to enter the market as a Greenfield deployment, basing its business exclusively on a wholesale model. There has been much discussion over the years of the threats posed to the traditional carrier model, with relegation to ‘pipe’ status seen by most operators as the worst case scenario.

las-vegas

Las Vegas, Usa

But Lightsquared—led by ex-Orange chief Sanjiv Ahuja—is embracing the model, using a combination of LTE and satellite technology (required by the spectrum licence), and outsourcing the deployment and operation of the network to Nokia Siemens Networks. The new player awarded NSN a contract worth $7bn over five years and its performance will be watched by many in the industry at a time when many carriers are looking at alternatives to the Capex intensive model of buying and deploying an entirely new network.

In his new book Being Mobile, Professor William Webb, director of technology resources at UK regulator Ofcom, argues that operators are under serious financial pressure to develop new deployment models.

“LTE comes at a difficult time for cellular operators. Cellular revenues are generally falling slightly, especially in developed countries, while at the same time data volumes are growing quickly. The resulting network congestion requires investment in additional capacity, but falling revenues suggest that further investment may be difficult to justify. Some operators are now questioning whether there is sufficient funding to enable competitive LTE networks to be deployed in a country or whether instead a single shared network to which all operators have open access would be a better model. Lack of sufficient spectrum for multiple LTE networks using 20-MHz-wide carriers in many countries is another factor making operators tend towards shared networks.”

While Lightsquared has pledged to refrain from any direct relationships with end users, the majority of carriers looking at LTE launches are working hard to try and establish what they hope will be attractive pricing structures for their new mobile broadband services.

In a bid to get as many people as possible to experience its new LTE offering, TeliaSonera’s initial strategy saw LTE service and dongles all but given away free of charge for the first six months. After this the price rose to SEK599/ month (e62) for the data-only service, which is definitely at the top end of what users in advanced markets typically spend on a monthly basis.

Metro PCS has said that the Samsung Craft will be available for $299, on two different LTE plans. Users are able to choose between a $55 plan including unlimited voice, texts and data access and a $60 plan with access to premium video-on-demand content and MetroStudio multimedia content. The flat rate data tariffs that operators have used to stimulate uptake of mobile data services have lost much of their appeal to carriers as networks have become overloaded by a small percentage of very intensive users and performance for all has been compromised. Tiered pricing looks to be the most popular alternative among the carrier community, and LTE offers the kind of leap in performance that operators need in order to usher in what will surely prove a comparatively unpopular pricing structure.

Speaking at the Nokia World event in September, Vodafone group CEO Vittorio Colao warned that the culture of what he called “free-ism” had to come to an end, with data-hungry applications such as streaming video and music needing to be priced in line with the demand they place on the network. Coloa’s speech coincided with the announcement from Vodafone’s German operation that it would be implementing such a strategy when it launches LTE service before the end of this year.

The carrier has opted to charge users by speed, as well as volume of data consumed. It will offer 10GB of data at 7.2Mbps for e40 a month, 15GB of data at 21.6MBps for e50, and 30GB at 50Mbps for e60.

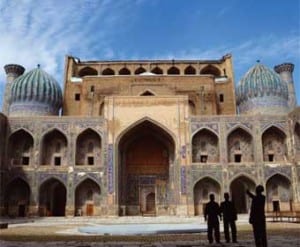

uzbekistan

Sher Dor Madrassah, Uzbekistan

Such a model highlights the focus on throughput speeds that have always been the industry’s favourite way of explaining the benefits of new network technologies. But the reality, says NSN’s Thorsten Robrecht, is that throughput will not necessarily be the greatest improvement that consumers will experience. “The big advantage from the end user’s perspective will be the latency,” he says. “In one of the networks we’re working on we’re now seeing round trip times of 13 milliseconds on real user traffic. That’s nearly three times faster than a DSL network, it’s really unbelievable.”

LTE is a data play for mobile operators, so it’s no surprise that it is the performance of the technology and the benefits it can bring in terms of data transfer that are at the forefront of discussions. But the mobile industry was built on voice revenues—and will remain in part dependent on them for some time to come—so the question of how to move voice traffic around in an LTE environment is an important one.

And as 2010 draws to a close, it’s a question that has met with no definitive answer. In February this year, carrier lobby group the GSMA announced its backing for the One Voice Initiative, a collaboration between AT&T, Orange, Telefónica, TeliaSonera, Verizon Wireless, Vodafone, Alcatel Lucent, Ericsson, Nokia, Nokia Siemens Networks, Samsung and Sony Ericsson, designed to create single standard voice delivery solution for LTE.

Absorbed into the GSMA, One Voice was rebranded as VoLTE (voice over LTE) and immediately gained the support of much of the enormous ecosystem over which the GSMA presides. “As mobile operators begin to deploy LTE, it is essential that their networks are aligned around one, common standard for voice and messaging services, for the benefit of the mobile industry and consumers alike,” said the GSMA’s CTO Alex Sinclair when the announcement was made.

But there remains the option to continue to use older networks to carry voice. While LTE is capable of carrying voice and SMS traffic, says Thorsten Robrecht, who says that one NSN customer required that their LTE network be voice capable from the outset—before the end of this year—it is unlikely that GSM networks will disappear from the scene anytime soon. “I don’t see anybody switching off their GSM networks yet, because it’s so widely deployed,” he says. “What I’m seeing from the LTE chipsets coming up is that it’s all about multimode. I see a long-term coexistence of GSM and LTE and I see a lot of operators also wanting to keep GSM as a basic voice service throughout the next ten years.”

Critics of the idea that operators should remain dependent on older networks argue that it could impact on the cost and efficiency benefits that new network deployments are intended to bring.

2010 has been a key year for LTE, with the first deployments gaining traction and proof, if it were needed, that the industry finally looks to be aligning around a single, worldwide cellular standard. But the technology still has to prove itself—crucially—under serious traffic loads. The idea that LTE provides the answer to the boom in mobile data traffic that we’ve witnessed over the last couple of years has been dismissed throughout the industry with the realisation that, whatever capacity is provided to the market will be consumed. Some voices can even be heard to suggest that LTE is simply going to make the problem of network congestion even worse.

Just as interesting as the technological issues at play is the fact that the introduction of LTE is going to test the new pricing and business models that operators need to implement to maintain and boost their profitability. The carrier community will care little for improved speed, latency or efficiency if they don’t lead to heftier revenues.

Fourth Coming

2010 has been a significant year for LTE as a growing number of carriers have prepared to join the handful of first movers in the deployment of the next generation cellular technology.

Before 2010 rolled into being, it was being touted by some as the ‘Year of LTE’. These kinds of taglines, as we’ve seen in times past, are notorious for coming back to bite the industry on the backside. Behind the bold proclamation, one often suspects, lies the triumph of hope over the plainly obvious. So it would be wrong to look back on 2010 in its closing weeks and judge it to have been LTE’s year—but that should not detract from the fact that it has been a very significant period for the technology.

As of the beginning of October there were four countries with commercial LTE networks in operation; Sweden, Norway, Uzbekistan and USA. There are 101 operator commitments to the technology across 41 countries, according to figures from the Global Mobile Suppliers Association, which also predicts that as many as 22 LTE networks could be in service by the end of the year, rising to 50 by the end of 2012. As 2010 draws to a close there is little doubt that LTE is the technology of choice for the next phase of the mobile data boom. And that status has come at the expense of a technology that was once expected to share the 4G market with LTE—WiMAX. One of the biggest wins for LTE came in the summer with the Indian Broadband Wireless Access spectrum auction. India had been one of the last big hopes for the WiMAX community, but strategic bidding and surprise technology decisions put a sizeable dent in those hopes.

Qulacomm led the blocking play, bagging 20MHz of spectrum in four key Indian markets— Delhi, Mumbai, Kerala and Haryana— and pledged straight away to use it for the deployment of LTE networks. “Our big bet is on LTE and we wanted to make sure that there was a place for LTE in India,” said CEO Paul Jacobs after the auction closed. “We were concerned that if both of those bands had gone to WiMAX it would have helped reinvigorate that ecosystem.”

The only nationwide winner in the BWA auction, Infotel Broadband Services, was acquired shortly afterwards by Reliance Industries Limited, whose CEO Mukesh Ambani revealed his own plans to launch an LTE service in its own 20MHz of spectrum. The BWA spectrum won by Qualcomm was unpaired and will therefore be used for the deployment of TD-LTE, rather than the FDD flavour of the technology that is being deployed on a larger scale in much of the rest of the world. But TD-LTE has been one of the big LTE stories in 2010, moving from what looked like a fairly niche proposition at the beginning of the year to a strong one as the final quarter begins.

Like TD-SCDMA before it, TD-LTE was thought likely at one stage to be restricted primarily to China. But, says Thorsten Robrecht, head of LTE Radio Access Product Management at Nokia Siemens Networks, it has emerged this year as a solution with a far wider range of potential applications. “TD-LTE is really a global LTE solution, I’m very sure about this,” he says. “It has evolved so much over recent months and now I’m seeing it appearing in all sorts of countries.”

While the standard has been incubated in China, Robrecht says, the earliest deployments are more likely to come from elsewhere. He reports significant activity in Japan as well as India and Russia and even customers considering it in Australia. But TD-LTE will lag its FDD sibling and all of the deployments so far—as well as the ones that are imminent—are in paired spectrum. Still, even deployments of the FDD-based version of the technology are not expected to gather truly mass momentum until sometime around 2012, with existing mobile broadband technologies like HSPA Plus still seen as having plenty of headroom. So what is driving the early deployments? What are the benefits of being the first to market?

One organisation that is well placed to answer that question is TeliaSonera which, in December 2009, became the very first carrier to launch LTE commercial services, with metropolitan networks in Stockholm and Oslo. It has since switched on LTE services in more cities in the two countries as part of its bid to hit 25 more metropolitan areas in Sweden, and the three next largest cities in Norway by the end of 2010.

Håkan Dahlström, the firm’s president of mobility services, was insistent that being the first to launch the new technology gave the firm a genuine competitive advantage over its peers. “LTE gives us the opportunity to give our customers high quality access and to really prove to our customers that going with TeliaSonera is a future-proven choice,” he told MCI earlier this year.

NSN’s Thorsten Robrecht is similarly convinced of the first mover advantage in the LTE sector. “We really see that there’s a race going on—a competition where the earliest carriers will win,” he says. “Just look at the rural coverage issues in Central Europe. The challenge for mobile operators is to beat the fixed carriers that are just offering voice. The first to come will be the one that gets the market, and operators are being very aggressive about this at the moment,” he says.

But for other operators, LTE is more of a strategic necessity than a chance to demonstrate technical prowess and leadership. Carriers that have followed the CDMA technology route, particularly in the US, do not have the luxury of HSPA, and the time and space it gives carriers to play with. So US CDMA players are more urgent in their approach to 4G technology.

It was a toss-up between market leader Verizon wireless and fifth placed Metro PCS—which is a regional rather than national carrier—as to which operator would be the first to launch LTE on US soil. In the end, it was the smaller player, driven by the fact that it had never taken the 3G step on the CDMA evolutionary path. Metro launched LTE in Las Vegas and then Dallas/Fort Worth at the very end of September. It was a double landmark, as Metro’s deployment saw the first appearance of commercial LTE handsets anywhere in the world, with previous deployments restricted to dongles for laptop users.

But analysts had words of caution for the pioneer carrier: “Metro PCS has put its name in the mobile history books by becoming the first mobile operator in the world to launch an LTE handset. But it’s a risky move because handsets using new mobile technologies take years to develop and this one is very early,” said Mike Roberts, principal analyst at Informa Telecoms & Media. “This could lead to problems such as poor battery life and dropped calls or data sessions, which happened with early WCDMA and WiMAX handsets.”

Samsung was the handset vendor responsible for the first LTE phone, The ‘Craft’ and Metro has said that it plans to have ten LTE handsets in the market by the end of 2011. The carrier hasn’t named any other suppliers, although it has signalled that Chinese vendors— presumably Huawei and ZTE among them—are pushing hard to get into the business.

Verizon is currently planning to launch in somewhere between 25 and 30 US cities in November this year, covering 100 million potential users. And like other early launchers, and perhaps with the kind of concerns set out above by Mike Roberts in mind, the US market leader has opted to launch with dongles and datacards, planning a handset-based offering some time in the first half of 2011.

The US was the site of another key LTE development during 2010, with the announcement that a new operator, Lightsquared, is to enter the market as a Greenfield deployment, basing its business exclusively on a wholesale model. There has been much discussion over the years of the threats posed to the traditional carrier model, with relegation to ‘pipe’ status seen by most operators as the worst case scenario.

But Lightsquared—led by ex-Orange chief Sanjiv Ahuja—is embracing the model, using a combination of LTE and satellite technology (required by the spectrum licence), and outsourcing the deployment and operation of the network to Nokia Siemens Networks. The new player awarded NSN a contract worth $7bn over five years and its performance will be watched by many in the industry at a time when many carriers are looking at alternatives to the Capex intensive model of buying and deploying an entirely new network.

In his new book Being Mobile, Professor William Webb, director of technology resources at UK regulator Ofcom, argues that operators are under serious financial pressure to develop new deployment models.

“LTE comes at a difficult time for cellular operators. Cellular revenues are generally falling slightly, especially in developed countries, while at the same time data volumes are growing quickly. The resulting network congestion requires investment in additional capacity, but falling revenues suggest that further investment may be difficult to justify. Some operators are now questioning whether there is sufficient funding to enable competitive LTE networks to be deployed in a country or whether instead a single shared network to which all operators have open access would be a better model. Lack of sufficient spectrum for multiple LTE networks using 20-MHz-wide carriers in many countries is another factor making operators tend towards shared networks.”

While Lightsquared has pledged to refrain from any direct relationships with end users, the majority of carriers looking at LTE launches are working hard to try and establish what they hope will be attractive pricing structures for their new mobile broadband services.

In a bid to get as many people as possible to experience its new LTE offering, TeliaSonera’s initial strategy saw LTE service and dongles all but given away free of charge for the first six months. After this the price rose to SEK599/ month (e62) for the data-only service, which is definitely at the top end of what users in advanced markets typically spend on a monthly basis.

Metro PCS has said that the Samsung Craft will be available for $299, on two different LTE plans. Users are able to choose between a $55 plan including unlimited voice, texts and data access and a $60 plan with access to premium video-on-demand content and MetroStudio multimedia content. The flat rate data tariffs that operators have used to stimulate uptake of mobile data services have lost much of their appeal to carriers as networks have become overloaded by a small percentage of very intensive users and performance for all has been compromised. Tiered pricing looks to be the most popular alternative among the carrier community, and LTE offers the kind of leap in performance that operators need in order to usher in what will surely prove a comparatively unpopular pricing structure.

Speaking at the Nokia World event in September, Vodafone group CEO Vittorio Colao warned that the culture of what he called “free-ism” had to come to an end, with data-hungry applications such as streaming video and music needing to be priced in line with the demand they place on the network. Coloa’s speech coincided with the announcement from Vodafone’s German operation that it would be implementing such a strategy when it launches LTE service before the end of this year.

The carrier has opted to charge users by speed, as well as volume of data consumed. It will offer 10GB of data at 7.2Mbps for e40 a month, 15GB of data at 21.6MBps for e50, and 30GB at 50Mbps for e60.

Such a model highlights the focus on throughput speeds that have always been the industry’s favourite way of explaining the benefits of new network technologies. But the reality, says NSN’s Thorsten Robrecht, is that throughput will not necessarily be the greatest improvement that consumers will experience. “The big advantage from the end user’s perspective will be the latency,” he says. “In one of the networks we’re working on we’re now seeing round trip times of 13 milliseconds on real user traffic. That’s nearly three times faster than a DSL network, it’s really unbelievable.”

LTE is a data play for mobile operators, so it’s no surprise that it is the performance of the technology and the benefits it can bring in terms of data transfer that are at the forefront of discussions. But the mobile industry was built on voice revenues—and will remain in part dependent on them for some time to come—so the question of how to move voice traffic around in an LTE environment is an important one.

And as 2010 draws to a close, it’s a question that has met with no definitive answer. In February this year, carrier lobby group the GSMA announced its backing for the One Voice Initiative, a collaboration between AT&T, Orange, Telefónica, TeliaSonera, Verizon Wireless, Vodafone, Alcatel Lucent, Ericsson, Nokia, Nokia Siemens Networks, Samsung and Sony Ericsson, designed to create single standard voice delivery solution for LTE.

Absorbed into the GSMA, One Voice was rebranded as VoLTE (voice over LTE) and immediately gained the support of much of the enormous ecosystem over which the GSMA presides. “As mobile operators begin to deploy LTE, it is essential that their networks are aligned around one, common standard for voice and messaging services, for the benefit of the mobile industry and consumers alike,” said the GSMA’s CTO Alex Sinclair when the announcement was made.

But there remains the option to continue to use older networks to carry voice. While LTE is capable of carrying voice and SMS traffic, says Thorsten Robrecht, who says that one NSN customer required that their LTE network be voice capable from the outset—before the end of this year—it is unlikely that GSM networks will disappear from the scene anytime soon. “I don’t see anybody switching off their GSM networks yet, because it’s so widely deployed,” he says. “What I’m seeing from the LTE chipsets coming up is that it’s all about multimode. I see a long-term coexistence of GSM and LTE and I see a lot of operators also wanting to keep GSM as a basic voice service throughout the next ten years.”

Critics of the idea that operators should remain dependent on older networks argue that it could impact on the cost and efficiency benefits that new network deployments are intended to bring.

2010 has been a key year for LTE, with the first deployments gaining traction and proof, if it were needed, that the industry finally looks to be aligning around a single, worldwide cellular standard. But the technology still has to prove itself—crucially—under serious traffic loads. The idea that LTE provides the answer to the boom in mobile data traffic that we’ve witnessed over the last couple of years has been dismissed throughout the industry with the realisation that, whatever capacity is provided to the market will be consumed. Some voices can even be heard to suggest that LTE is simply going to make the problem of network congestion even worse.

Just as interesting as the technological issues at play is the fact that the introduction of LTE is going to test the new pricing and business models that operators need to implement to maintain and boost their profitability. The carrier community will care little for improved speed, latency or efficiency if they don’t lead to heftier revenues.

Read more about:

DiscussionAbout the Author

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

_1.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)