LTE: Strong Starter

Compared to its predecessors LTE has shot off the starting blocks but it remains a very small part of the overall mobile market. Telecoms.com offers an overview of the current situation and picks out some of the challenges that require further attention.

June 24, 2013

At what point does a cellular network technology become mainstream? LTE, as we are often told, has outstripped its predecessors in terms of deployment, making it the fastest mobile technology in history in terms of uptake as well as throughput. Research from the Global Mobile Suppliers Association published in April counted 175 commercial networks in 70 countries at the end of 1Q13. It has taken a little over three years to reach this point; an impressive achievement for the industry.

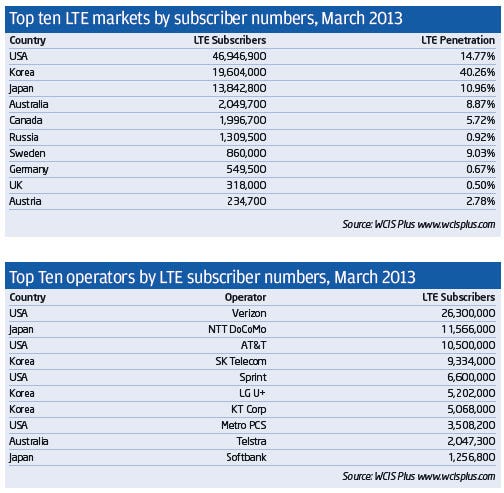

But LTE remains a minnow in relative terms. First quarter 2013 data from Informa’s WCIS Plus put global LTE subscriptions at 95.3 million, which accounted for 1.46 per cent of the overall cellular market. At the end of the year, Informa forecasts, it will be the fifth largest network technology, behind GSM, WCDMA, CDMA and—by a whisker—TD-SCDMA. Four years on, at end 2017, Informa predicts that LTE will be nudging one billion subscriptions, having overtaken the dwindling CDMA and the slower growing TD-SCDMA.

The maturity of LTE is also relative in geographical terms; in the leading markets of the world uptake is flying. The US accounts for over half of all current LTE subscriptions while, in South Korea, LTE has more than 40 per cent of the market. Japan is the third of the leading markets and, with 13.8 million LTE subscriptions, oversees the considerable gap between the top three and the chasing pack; Fourth placed Australia has 2.05 million LTE subscriptions. Most of the leading LTE operators have been driven by necessity, with CDMA technologies nearing the end of their lifespan.

There is plenty of headroom remaining on WCDMA networks that have evolved towards HSPA, which is leading to a less aggressive approach from operators in other mature markets—particularly in Western Europe. So despite having less than a quarter of a million LTE subscribers, Austria still makes the top ten LTE operator listing.

Operators report that, technically, LTE deployments have not been unusually demanding. Michel Lenoir, programme manager for LTE at Vodafone Netherlands says that his firm’s rollout was “broadly comparable to the move from 2G to 3G” while Mock Pak Lum, chief technology officer at Singapore’s StarHub, says that, for his organisation, it was actually easier. “Because it is all IP,” he says, “it is not as painful as rolling out 3G.” But there has long been a sense that the technology element of LTE would be nowhere near as challenging as the business of making it pay. At the 2012 LTE World Summit Orange Spain CTO Eduardo Duato addressed this issue in the frankest terms, suggesting that many operators—particularly in the markets hit hardest by macroeconomic difficulties— would be incapable of deriving a return on LTE without taking network sharing to previously unexplored depths.

Despite Orange having calculated the total cost of ownership for LTE as 30 per cent lower than 3G, Duato’s warning was dire: “We are unable to really come up with a solid business case for LTE; we see only erosion in the years to come,” he told event delegates.

Unable to decommission their legacy networks “for a very long time”, established European operators are going to be hit hard by the cost of managing three generations of network technology concurrently, he said. Duato captured one of the key differences between GSM operators’ LTE deployments and those of CDMA leaders like Verizon and SK Telecom. Ex-CDMA operators are highly motivated to migrate users to LTE as fast as reasonably possible because there is no other option. Necessity will enable them to reap the cost efficiencies of network consolidation more quickly than their GSM-based peers.

GSM will remain in place for many years yet, not least to facilitate the roaming services that were so fundamental to its selection and success (CDMA operators, meanwhile, have been well used to workarounds for roaming). While GSM operators argue that they will harvest the benefits traditionally associated with following rather than leading in any technological evolution, they will not be able to exploit a single, or even dual network portfolio for some time to come.

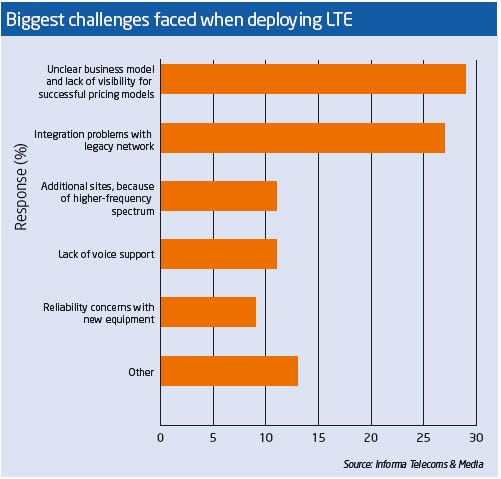

Indeed in a recent survey of European operators conducted by Informa, integration problems with legacy networks was rated the second most serious challenge that operators face in deploying LTE. The first was an “unclear business model and lack of visibility for successful pricing models,” suggesting that—one year on—Eduardo Duato’s concerns remain valid. LTE has already influenced pricing behaviour from operators, with recent developments including shared or multi-device plans, contextual upgrades and moves to separate device cost from service cost, allowing operators to extricate themselves from the burden of device subsidy. Yet competition remains intense and not all operators are looking to LTE to provide premiums. Earlier this year the UK arm of Hutchison’s 3 announced that it will not price LTE services at a premium to its existing offers. In a nod to the higher charges levied by UK LTE market debutante EE, 3UK said: “Unlike some other UK mobile operators, [LTE] will be available across all existing and new price plans without customers needing to pay a premium fee to ‘upgrade’.”

Meanwhile EE cut its prices in January, well aware that its first-mover advantage is shortly to expire—and it is clearly trying to attract as many users onto long contracts as possible. But EE’s price cuts and 3UK’s announcement reflect the fact that users are not widely inclined to up their spend for faster network access.

“If the price of a service is well above a consumer’s income or disposable spending levels then they are simply not going to buy it,” says Jaco Fourie, senior BSS expert at Ericsson. “If you have more than 100 per cent penetration in a market then you might get a bump from the early adopters when you first launch [a new technology] but when you get to the mass market you will grow at GDP—end of story.”

Nonetheless there is optimism out there, if you know where to look. Vodafone Netherlands’ Michel Lenoir says that, while the firm’s initial deployment of LTE at 2600MHz in 2012 was a small-scale sop to licence obligations, its current move towards deployment at 800MHz and 1800MHz is “based on the commercial belief in the return on investment for LTE.” Nokia Siemens Networks’ head of portfolio management Thorsten Robrecht says that belief in LTE has improved enormously over the last year. “It is a really big surprise how much LTE has really boosted,” he says. “In terms of deployments [the industry] is so far above our own expectations and forecasts that RoI does not seem to be a problem. At the end of 2012 we had 52 LTE customers. By Mobile World Congress [in February] we had 78.”

Whatever positive shifts may be taking place in the collective industry mindset—and however comfortable CTOs feel with the deployment of LTE—significant challenges must still be met, not least at the very heart of the mobile proposition. LTE is a data technology designed to move rapidly increasing volumes of data traffic. But voice communication remains essential to the mobile proposition and solutions—both interim and permanent—are of critical importance.

Here again the split between operators of the GSM and CDMA bloodlines becomes apparent. GSM players have fallback options that offer a comfortable safety net for voice communications while the CDMA camp, once again, is motivated to migrate to new standards at more of a gallop. There are numerous ways to enable voice on an LTE, device, however and the familiar industry issues of fragmentation and interoperability are rearing their head once more. For a detailed exploration of the VoLTE landscape, see our feature on page 12.

Here again the split between operators of the GSM and CDMA bloodlines becomes apparent. GSM players have fallback options that offer a comfortable safety net for voice communications while the CDMA camp, once again, is motivated to migrate to new standards at more of a gallop. There are numerous ways to enable voice on an LTE, device, however and the familiar industry issues of fragmentation and interoperability are rearing their head once more. For a detailed exploration of the VoLTE landscape, see our feature on page 12.

Related to voice and no less fundamental to what mobile has come to represent is roaming. In the past new mobile network technologies have enjoyed lengthy grace periods during which they could bed in before anything other than basic functionality was required of them. Today’s end users, enterprise and consumer alike, are quick to demand ubiquity for any service improvement bestowed upon them—and they expect cross-border support.

At Mobile World Congress this year Greg Dial, director for global roaming at Verizon Wireless, told MCI that his brief for the show was to identify potential roaming partners in popular overseas markets.

“We are surveying the market and looking at our travel centres to see where US customers are going,” said Dial. “It’s a wide variety of destinations but certainly the UK is a market we look at very closely; the Caribbean and Latin America too and Canada. We’re still in the planning stages, but we’re here at MWC building relationships for 4G LTE roaming, both outbound but we’re also open for business for inbound roaming as well.”

LTE roaming is somewhat obstructed by the variety of spectrum bands that are allocated to the technology in different markets—a sizeable caveat to the notion of LTE as a single global standard. To complicate matters, operators are so concerned about spectrum shortages that they are buying whatever they can get their hands on in the hope that future network technologies—carrier aggregation in particular—will magically link them together somewhere down the line.

Historically operators have looked to device vendors to address the problem of multiband compatibility. With LTE the device vendors find themselves in a far more powerful position than they did when operators were demanding tri-band GSM ‘worldphones’. Indeed Apple’s decisions on which bands to support with its first LTE capable iPhone were heralded by some as likely to drive operators’ spectrum acquisition strategies.

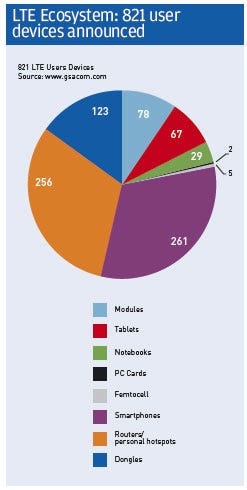

The device ecosystem has developed at a phenomenal pace compared to previous technologies, with the GSA reporting in March that 821 user devices, including frequency and carrier variants, had been announced by 97 manufacturers. The number more than doubled over the year to the end of March, with the number of vendors also growing by 54 per cent. And while routers and dongles account for a substantial share of these devices, there were 261 smartphones in the mix.

The debates surrounding LTE today are more about routes than destinations. We know that the technology is the future of the world’s mobile operators, we know that it is capable of achieving what it has been designed to achieve and we know that some operators, at least, will make it pay. But there are different ways to approach different problems that remain to be solved. Operators’ choice of paths will go a long way to determining their success.

Read more about:

DiscussionAbout the Author

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

_1.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)