New research claims employees do not own HuaweiNew research claims employees do not own Huawei

Two academics researched the ownership and control structure of Huawei and concluded the company is not owned by employees, contrary to what the company has officially claimed.

April 16, 2019

Two academics researched the ownership and control structure of Huawei and concluded the company is not owned by employees, contrary to what the company has officially claimed.

Christopher Balding, an Associate Professor of Economics at Fulbright University Vietnam, and Donald Clarke, a Professor of Law at George Washington University’s Law School, published a preprint paper titled “Who Owns Huawei?” on SSRN, the online sharing platform for scholars. The scholars combed the publicly available information, from both China and overseas, and pieced together a picture of Huawei’s ownership and control structure.

Huawei has repeatedly stated that the company is jointly owned by Ren Zhengfei, the founder, who has 1.14% of the share, and the 100,000 or so employees who own the rest. “Huawei is a private company wholly owned by its employees”, says the company’s annual report. The company “involves 96,768 employee shareholders”. The founder repeated the message at his interview with a group of journalists from the global media earlier this year. The scholars dug into the opacity and found the reality is more complex and less clear.

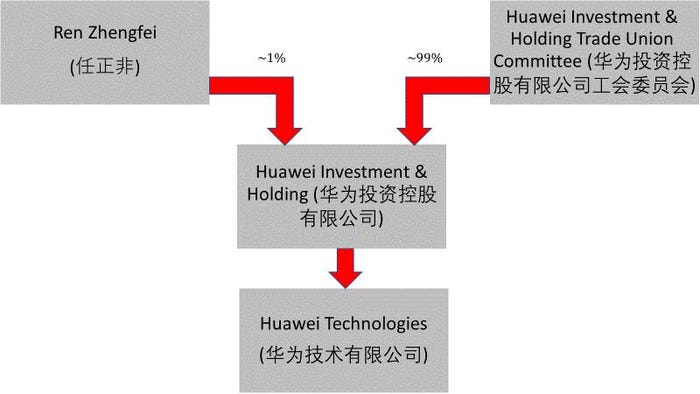

They started with distinguishing the different entities enshrined in the name. Huawei Technologies is the company that produces and sells products and services, and employs around 188,000 people (according to Huawei’s 2018 Annual Report). This entity is 100% owned by a holding company called Huawei Investment & Holding Co., Ltd., which employs no more than a couple of hundred people. Ren Zhengfei owns 1.14% of the holding company, the rest is owned by an organisation called Huawei Investment & Holding Company Trade Union Committee (the scholars abbreviated the name to “Huawei Holding TUC”).

There is no information on how Huawei Holding TUC is constituted or what the governance model or decision-making process is. Probably more importantly, the TUC is associated with the holding company (which employs a couple of hundred people), not with Huawei Technologies (which employs 188,000 people). Even if all the employees under Huawei Technologies are represented by the TUC, according to the labour law in China, “trade union officials are appointed by management or by the administratively superior trade union organization, not chosen by the members.” (P.9) In other words, the employees cannot decide who can sit on the committee, less how they make decisions.

The authors of the paper also attempted to separate ownership from control, or in a hypothetical case of insolvency, right to claim to company’s residual assets. Again, according to the law in China, “residual assets of a trade union go up, not down, to the trade union organization at the next highest administrative level” (P.9), theoretically all the up to the “All-China Federation of Trade Unions at the central level. The Communist Party controls the ACFTU, with the head of the ACFTU sitting on the Politburo.” (P.10)

There is further opacity related to how the boards are created. In the official transcript of the founder’s interview distributed afterwards, one can read that recently Huawei underwent a year-long voting process among the “96,768 shareholding employees” to select the 115 members to the Representatives’ Commission, which, according to the owner, “is the highest decision-making authority in Huawei”. This Commission then would select Huawei Holding’s Board of Directors and Board of Supervisors. But here is another ambiguity, as the authors of the paper pointed out: if the shareholding employees vote as shareholders, then their votes should be weighted; if they vote as employees, then all employees shareholding (about 100,000) or not (about 90,000) should have the chance to vote.

This points to the true nature of the “shares” the 100,000 or so employees own. The scholars found that, after a few stages of historical morphing, the shares are no more than stock options public listed companies incentivise their employees with. In other words, the employees do not own a part of the company through their “shares”. Instead, the “virtual stock is a contract right, not a property right; it gives the holder no voting power in either Huawei Tech or Huawei Holding, cannot be transferred, and is cancelled when the employee leaves the firm, subject to a redemption payment from Huawei Holding TUC at a low fixed price.” (P.5). The owner said in his interview that shareholding employees also include “retired former employees who have worked at Huawei for years.”

The two factors put together, the opaque governance model of Huawei Holdings and the lack of ownership associated with the shares half of the employees own, led the scholars to the key conclusions. First, though they could not be sure who actually owns Huawei, they are pretty sure the employees do not. Second, the lack of transparency of the governance model of Huawei Holdings looks to put Huawei between a rock and hard place.

On one side, the authors commented, “if Huawei Holding is in fact controlled by a trade union committee, then given the way such bodies are supposed to operate in China, it makes sense to think of it as state-controlled and even state-owned.” (P.12). Otherwise, if Huawei Holding is not actually owned and controlled by the trade union or its committee, Huawei has not been telling the truth. Then it is up to Huawei to make its case. “The information necessary to do so is in Huawei’s control,” the scholars said. (P.11)

Get the latest news straight to your inbox. Register for the Telecoms.com newsletter here.

About the Author

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

_1.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)