Africa: The road to m-government

According to the E-Government Survey published by the UN in 2010, although African countries generally lag behind other markets in the rankings of e-government implementation, there has been improvement in the region since the 2008 survey, particularly in northern Africa. Tunisia and Egypt were two of the highest-ranked countries in Africa alongside Mauritius, South Africa and Seychelles.

November 21, 2011

africa-usage

According to the E-Government Survey published by the UN in 2010, although African countries generally lag behind other markets in the rankings of e-government implementation, there has been improvement in the region since the 2008 survey, particularly in northern Africa. Tunisia and Egypt were two of the highest-ranked countries in Africa alongside Mauritius, South Africa and Seychelles.Looking at the e-government strategies of many African countries, it is clear that there is a will to be in the vanguard of the region’s e-government movement. The Kenyan government recognises that e-government can be “an economic pillar, a social pillar and a political pillar.” The South African government pledges that it will have 50 services automated on e-government platforms in 2014 and has articulated the need for greater “citizen engagement”. In North Africa, Algeria’s 2013 strategy refers to the development of online services for the benefit of its citizens, as illustrated by the government’s H1N1 National Hotline, a portal page with a section for citizens to access medical resources and share information on symptoms to monitor for the H1N1 flu.

Judging from this, policy makers from parts of the region have reacted to Connect Africa – but what of the view from the industry? In a survey commissioned by Informa Telecoms & Media in June 2011, two-thirds of the respondents felt that e-government services remained undeveloped in Africa. In the same survey, two thirds of the respondents said they believe that education and payments are the most important potential services that could benefit from a state’s e-government policy. This is interesting as it suggests C-level executives feel that governments should not only use e-services to benefit their citizens (education/training), but could also use ICT to transform the government’s own internal processes (payment of public sector staff) by creating greater efficiencies.

When looking at e-government strategies in Africa, something is particularly striking: there is no clear articulation of the potential role that mobile devices can play in the spread of e-government services. Given the role that mobile has played in the African economy and culture in the last decade, this is strange.

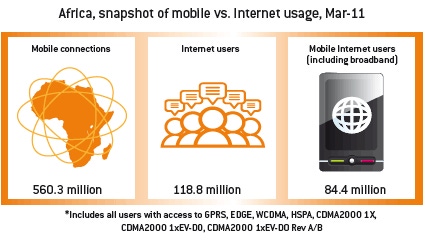

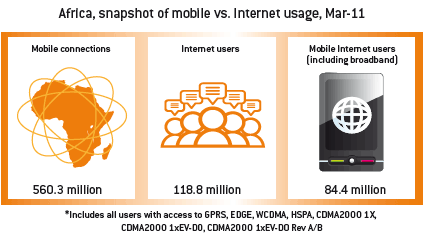

The mobile revolution has brought communications to hundreds of millions of people across Africa within a short period of time. At the end of 2001, there were just 25.6 million mobile subscriptions across the whole of Africa, representing three per cent penetration. Informa projects that by the end of this year – ten years later – there will be 640 million subscriptions across the continent and SIM penetration will be close to 60 per cent. Strange then for policy strategists to overlook mobile as a tool in building greater engagement with citizens and for governments not to benefit from potential efficiencies that mobile government can create. Is building a strategy around e-government (while excluding mobile government) sustainable when, according to figures released by Informa, household broadband penetration in Africa is just 3 per cent and is projected to grow to 8 per cent by the end of 2016? Governments and businesses are learning to accept that consumers expect an anywhere, anytime service. The emergence of wireless technologies and development of mobile applications in Africa means this anywhere, anytime expectation has become an African reality too.

The implementation of e-government can create a greater visibility to the government citizen relationship and allow governments to become more efficient and effective in fulfilling their service-delivery functions. This is the reason for the focus of one of Africa Connect’s goals being around e-government.

So what of mobile government? In many countries such as Estonia, Germany, Singapore and Hong Kong, it has become a key element of e-government through its “utilisation of wireless and mobile technology, services, applications and devices for improving benefits to citizens, businesses and government units” (Ibrahim Kuschchu of Mobile Government Consortium International, 2003).

It is easy to suggest that the move from e-government to m-government is inevitable, but this is especially the case in Africa, where the number of people with access to mobile phones is growing, and exceeds the number of citizens with access to the internet by nearly five to one. This is particularly the case in rural areas of Africa, suggesting the need for mobile government is even greater for approximately 60 per cent of the continent’s population.

The beneficiaries of mobile government can be classified as governments, citizens and businesses: Government departments (G2G): Applications and services can improve organisational and business processes, such as making in-field mobile workers more productive, encouraging the use of videoconferencing or providing secure co-partner services with other agencies (e.g., NGOs).

The single most effective communications tool for stimulating the greatest demand and supply of public services in Africa is probably the radio. Its reach is wide, it delivers content in local languages, it provides information to the illiterate, it requires only small amounts of electricity and people recognise it as a traditional and trusted supplier of public information. But radio as an instrument of government information and services has its limitations: The key to e-governance is a two-way communication between citizen and government, or business and government. Other requirements for effective e-governance include accessibility to a wide audience and the need for content to be accessible over a wide range of formats. The mobile device meets these requirements: it allows for speedy interaction; access to mobile telephony has become ubiquitous in many of the continent’s markets; and the use of SMS, USSD and IVR gives the mobile phone the edge over the PC as a public service delivery vehicle.

Mobile operators have become the main providers of internet services in Africa. Informa expects mobile to dominate broadband services in terms of user numbers as a result of recent infrastructure investments in 3G and 4G networks.

It is instructive too to look at Informa’s projected shift of internet traffic. While fixed internet traffic exceeds that of mobile internet, the gap is reducing markedly in Africa, so much so that, by 2015, Informa projects that 18 per cent of its internet traffic will be carried by cellular networks compared with a global figure of just 3 per cent. The fact that mobile networks will be able to host higher bandwidth-intensive services over the course of this forecast period helps to explain this transformation.

Messaging services and other non-voice services are already popular with consumers as the mobile device becomes a central platform for greater interaction, service delivery and internet access. This will continue to be encouraged by mobile operators as non-voice services are a way of offsetting the decline in their voice-based revenue. The success of mobile government will depend on the willingness of consumers to conduct more messaging, browse the internet with a portable device more regularly and access utility services with greater frequency. The limited functionality of entry-level handsets is an inhibitor to the potential of mobile government services. However, the smartphone market is set to grow in Africa too. According to projections from Informa, over a third of mobile connections in South Africa will be via smartphones by the end of 2016, and this figure will be in excess of 15 per cent in Egypt, Kenya and Nigeria. This provides far greater flexibility to what can be achieved by mobile government.

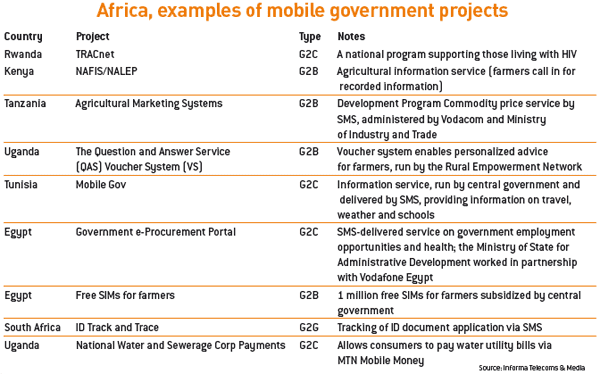

africa-gov

Starting the mobile government journey

Despite a lack of policy frameworks on mobile government, there are a number of mobile government projects in place across Africa. In some cases it is the private sector driving forward the mobile government agenda. IBM is working closely with the Kenyan government in shaping the framework for the organization of its data-management systems and enabling better citizen access.

This is an important pillar in the Kenyan government’s drive to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the delivery of some of its services, using computers and mobile phones as a means of delivery.

HP is about to ramp up its investment in sub-Saharan Africa and it sees public sector as an important part of its strategy for growth for the region. Examples of its work include improving disease surveillance through mobile health monitoring technology in Botswana and the deployment of a technology platform providing education to those without access to formal schooling in Senegal.

And yet, such examples are still few and far between. Mobile government has been slow to take off: governments typically hold short-term views with their plans to use technology to improve efficiency and effectiveness often fizzling out though lack of funding and often lack of expertise. Educating government as to how it can benefit from mobile technology is paramount – as is informing the general public. As the growth of mobile banking tells us, if there really is a need for a type of service, people will use it in their droves.

There is a technology concern too. Servers are required for electronic records and enabling dynamic access to information requires record-management software and better internal ICT integration. To get to this stage is expensive and once again requires expertise. With funding available from donors, foundations and multilateral agencies, perhaps it is here – in training and supporting ICT integration – where they can make a real strategic difference. Which African countries are ready for mobile government?

In launching a mobile government readiness index, Informa Telecoms & Media has attempted to identify those markets that are most ready to implement mobile government. Live implementations have not been scored for the index, which instead ranks those countries that have the cellular technology landscape, state policies and consumer appetite required to allow mobile government to work.

The parameters used for the rankings are: • Mobile penetration illustrates cellular accessibility and potential reach of mobile government services (G2C).

• 3G penetration reflects the maturity of cellular networks and the ability with which mobile government services could be used for more than SMS delivery. With the exception of South Africa, access to 3G services remains very limited, suggesting mobile markets still remain largely immature. Mobile government deployments therefore need to remain simple to be effective for the G2C market.

• Mobile broadband penetration forecasts highlight projected consumer demand for data-intensive services. This score acts as a proxy as the fact is that mobile broadband is largely based on dongle rather than handset usage.

• The percentage of the population living in rural areas is included on the basis that mobile government is particularly useful in reaching out to consumers in rural areas. One of the most compelling arguments for mobile government in Africa is as an attempt by the government to engage with citizens that currently have little government contact, and are frankly expensive to reach out to. The fact that three-quarters of the population lives in rural areas in Uganda, Rwanda, Kenya and Tanzania is a big incentive for certain public services to be delivered with the help of cellular technology.

Which countries are ready?

It is perhaps no surprise that South Africa sits at the top of the mobile government readiness index. And yet, mobile government has been slow to take off there, with governments in Rwanda, Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania quicker to embrace the consumer benefits of public service delivery by cellular technologies. There is some world-weariness and cynicism in South Africa as to whether mobile government will take off, while at the same time there is real anticipation as to the benefits and revenue that it can bring.

For mobile government to take off across the whole continent there needs to be a success story in South Africa. But, the cynic suggests that the industry has been discussing this issue throughout the decade and there has been little action to go with the talk.

In 2007, MTN Business and South Africa’s State Information Technology Agency (SITA) signed a partnership which both parties hoped would result in secure mobile and network solutions for multiple government departments enabling more rapid citizen-service delivery. Instead the hoped-for MOBiGOV service stalled.

Despite this, SITA remains adamant that it wants South Africa to become a world leader in mobile government and is in the midst of developing strategy aimed squarely at aligning mobile government with e-government. The focus of providing facilitated access to government services for all will be via cellular technologies.

For now, though, talk about mobile government implementations in Africa, and instead you think of action from governments in Uganda or Egypt. Here, the governments have worked closely with MTN and Vodafone, respectively, in allowing customers to pay their water bills to the state-owned incumbent using MTN Money, and in delivering services around government employment opportunities. If the continent of Africa is ready for mobile government, the state will have to work with the private sector in ensuring that political vision becomes action.

Read more about:

DiscussionAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

_1.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=800&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)